March 24, 2021

Artist to Watch

Ilana Savdie

NB: You have been working at the prestigious NXTHVN Residency in New Haven, Connecticut for the past year. What has been your greatest learning throughout this process? Can you tell us a little about the ambition and purpose of the residency?

IS: The residency is in year two, so it’s still growing and evolving. The main ethos that seems to permeate is about creating a space where very early career artists can receive the kind of mentorship that is otherwise hard to access. It was founded by Titus Kaphar, he makes a great effort to unlock a lot of the ‘secrets of the trade.’ There are many things that are withheld or passed down only to an elite few in this world and Titus really wants to create an environment where that process is democratised in a different way. I’ve learned a tremendous amount about what it means to engage with the people that give me the platforms to share my work, such as galleries and collectors while retaining my sense of self in my studio so I can continue to think about how I make my work, about painting, and about my place in the history of art, if I get the privilege of having one.

We learn how to engage with people that actually have power in this industry in a way that someone, early in their career, has not experienced yet. It has also been a discovery process for myself and realizing that actually I do have power, and it turns out, a lot more power than I originally thought — that shift was a big one for me. Artists have a lot of power if we just talk to each other, if we communicate our experiences, I believe this is what helps takes the keys away from toxic people. And in a more personal way, I have learned very much about what it means to trust my own instincts, both in my work and with people.

NB: So NXTHVN really provides that supportive environment that can really prepare artists as they transition from the institution of the university to the art world, and it provides that business experience, expertise, and insight to how the art market and its players interact and how you can best work with them?

IS: Absolutely, there’s definitely an understanding that this is your job, and there is no shame in acknowledging that you want to live off of it. For some reason, people like to shame artists out of financially supporting themselves through their own work, and I don’t subscribe to that. To each their own, but I think at the end of the day we all need to pay for health insurance in this country, at the very least, not to mention that making art is expensive. Everybody has a different way of approaching their work. But money is exchanging hands, going into someone’s pocket, I believe in the artist getting to have a pocket. In order to get there though, you have to know what it is that you’re working with — whether you want to make changes to the industry from within, subscribe to it and perpetuate it, or burn it all to the ground. Whatever it is, this is the [art] market and this is how it works, and NXTHVN is definitely a place that doesn’t shy away from the uncomfortable conversations about what you’re walking into.

NB: Last time I was at your studio, I got a glimpse into your powerful new body of work and we talked about how you tapped into your childhood memories. Do you want to tell us a little about that, and specifically about the character that features throughout?

IS: I grew up in Colombia, as did my mother and most of my family, yet nationality has always been a complicated subject for me. My family is all Jewish and from all over the world, so they ended up in Colombia as a result of many different diasporas. My father is Egyptian and my mother is Venezuelan, but her family is Romanian and Polish, and all were expelled or escaped from their respective countries, so I actually have a very complicated relationship with the idea of heritage. I have a very personal relationship, and a very acute relationship, with what it means to grow up in a place, to leave that place, and to have it exist as memory, the uncanny feelings of having home be both familiar and unfamiliar.

The experience of placelessness is a big aspect of my work, and informs how I approach any sort of ‘truth’ in the paintings. My work doesn’t deal with any particular nationality because I don’t really have one— landscapes and geographies do not really apply to me. With that in mind, I was deeply impacted by the experience of growing up Colombian, and specifically growing up surrounded by the Carnaval de Barranquilla, which happens in my hometown every year. Barranquilla is the city that hosts the second largest carnival in the world so while it’s only three days a year, it leaks into the culture of the entire coast. The ethos of the carnival has had such a strong impact on who I am, who I grew up around, and how I approach things. The idea of resisting and flipping social norms, of using the exaggeration of the body as a way to mock, to resist, and to protest oppressive boundaries; the grotesque body and idea of ‘the uncanny’ as an access point. All these things that are true to the carnival feel true to how I approach my work. These are themes and acts that I’ve located myself, my identity and my experience though, and they’ve permeated my work, through color, in a major way. Lately I’ve been working with the features of marimonda, a prominent figure of the Colombian carnival, which always fascinated me as a child. I use the features of the marimonda, which are big eyes, a floppy nose, big lips, which are said to be the combination of a number of different animals but it has this really phallic appearance; it looks like human genitalia, it is really strange. I bring in these features in part to locate figures in the work. The origin of the costume is said to have been a way to mock the oppressive elite of the time. Of course, as with any kind of folkloric history, it is passed down through word of mouth, so a lot of things aren’t historically concrete, but that’s the way it’s said to have been. In recent years it was brought into the carnival, so I am also really interested in its history, and it’s evolution.

NB: Tell us a little about your exhibition at Deli Gallery where you just had a sell out show, congratulations! Can you speak to that body of work, and how everything that you’ve just talked about translated into the show?

IS: My work deals with the body in all its different states, that includes all the things that live on the body. It poses the question of: who gets to have a body? What constitutes a body, and where does it start and end? If we are our bodies, we are also all the things that live on us — we are our viruses, our parasites, we are everything that threatens and consumes us; we are in a constant state of flux. The original idea was for the show to be a series of small paintings, all around 16 x 20, focusing on the microscopic bodies as the real estate in the paintings. As I started to develop this work, I realized that I didn’t feel ready for a show that only focused on that because I’m still at a state where it’s about the simultaneity of all bodies and organisms and identities coexisting and propelling power as they locate home, history and heritage. The show very quickly became about focusing on that process. I’m thinking of the way I make these paintings as creating paths for these bodies, and then derailing those paths. I’ve been thinking about this show as that process of derailment, and really showing different elements and different moments of that process throughout the space.

NB: The deconstruction of the body has been a theme in your work for a long time, since I first met you, including plastic surgery techniques and how they could be incorporated abstractly into painting. The way in which you approach the body is so fresh, and then your use of the color palette on top of that is gorgeous. I have the pleasure of living with two of Ilana’s works.

IS: Yes, that’s true you have two different stages in the evolution of this work! I think this concept is definitely something I am going to work with for a very long time. I don’t know how to exist in the world without being fully aware of my own body at all times. I think it comes from always feeling that I’ve been given a box that was too small, a chair that was too small, or a boundary that was too small. Being told — in the context of my body and my identity — to take up as little space as possible; I am never not aware of how I spill out. I’m going to call that a huge privilege of having a big body: I get to know my environment more, I get to know every space I’m in, and I get to make these paintings from that [experience]. I am always going to break it down. I am always going to break down the body because it doesn’t make any sense to me.

All the figures in my work are multiple figures, and they’re also all the same figure. That is what I mean by ‘untruth’ — the process of one ‘truth’ ‘untruthing’ another, but also never really allowing for that to happen. There is always going to be more than one body, but it’s just a matter of what constitutes a body. But then, at the same time, I consider them all the same body and also all real estate for more bodies. There is a constant in that they all have the same features but aside from that I don’t isolate into a gesture. I try to use as many different ways of thinking about and applying paint as possible, so I don’t separate figures from environments. I don’t separate figures from each other through gestures, so it really becomes about how I like to have [the work] constantly delivering different things the more time you spend on it. As soon as you decide that you’ve found something, it’s derailed, and you’re somewhere else. I want that to be a constant spinning wheel or something.

NB: What’s next for you? You just mentioned that this is an area you’re going to continue to work in for a while, are you planning to expand this series? What does life after NXTHVN look like?

IS: Yes, I am actually working toward another solo show this year. This one is going to be at Kohn Gallery in LA. I am going to say it’s a continuation of this series, for sure, because these are works that I have been doing simultaneously. They are going to be larger paintings. In larger spaces, I am able to expand on the figure much more. I like to think of the body as real estate for more things, more bodies, more gestures and more textures. More space for these bodies, and more bodies for this real estate. So I am excited about that, that is sort of the focus at the moment. So, post-NXTHVN it’s going to be about continuing this work!

February 16, 2021

Artist to Watch

Kevin Brisco:

Kevin Brisco:

Beauty and Absence

NB: Why don’t you tell us about your story up until you were accepted into the Yale MFA Program?

KB: I was born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, same house 18 years. I grew up in a very religious household, Seventh-day Adventist and Baptist. So I would go to church twice every weekend. From there I ended up going to undergrad in Connecticut at Wesleyan University. I was originally studying Political Science and Arabic and was convinced I would be a Foreign Service Officer. Low and behold I ended up taking art courses and found my passion. This is where I was willing to stay up all night to get the work done. From there I moved to New Orleans, where I worked in the film industry as a lighting technician. It was a wonderful gig, where you’re on set for a couple months and you have enough money for the year, so I could keep painting. I really enjoyed it in Louisiana. I was showing and receiving attention for my work. I had the feeling that “Ok, this could be a successful career.” However I felt that there were still a lot of gaps in my knowledge. There’s the things you know you don’t know and then on top of that there are the things you don’t even know you don’t know. I figured it was as good a time as any to reapply to grad school. It was my second time applying. I applied to Yale after undergrad and was waitlisted after a difficult interview experience. The second time I interviewed and had a much more generative experience. In the span of a 30 minute interview the two professors asked questions about my work that I had never considered. Finally I was excited at the possibility of attending because here was a place that I could undoubtedly learn some things I didn’t know I didn’t know.

NB: What types of themes do you explore in your work? How has your journey of growing up in the South, going to school in Connecticut, and working in New Orleans contributed to your practice in the last two years?

KB: In the most simple sense, I’m interested in figure-ground relationships. Particularly the background of the South, the American U.S., and how written into the landscape is the history and narrative of the figures occupying it. It allows the space of imagination within the landscape. You aren’t immediately given the histories of the traumas but you can sort of see the history or legacy of it through the shadows. Light and shadow are also an important theme, and the conception around light being historically seen as knowledge, safety, and awe-inspiring. I’m interested in the idea that difficult things can still happen in broad day-light. Questions of joy and trauma are all wrapped into one. I think its Saidiya Hartman, a Wesleyan and Yale alum, she was talking about how she wasn’t interested in displaying outright trauma but rather the spaces where celebration and tragedy are so intertwined you can hardly separate them. I’m interested in this idea of light as both a harbinger of safety but at the same time, light casts shadows. You can’t have shadows without light. Light is intrinsically tied to falling out of view or being hidden.

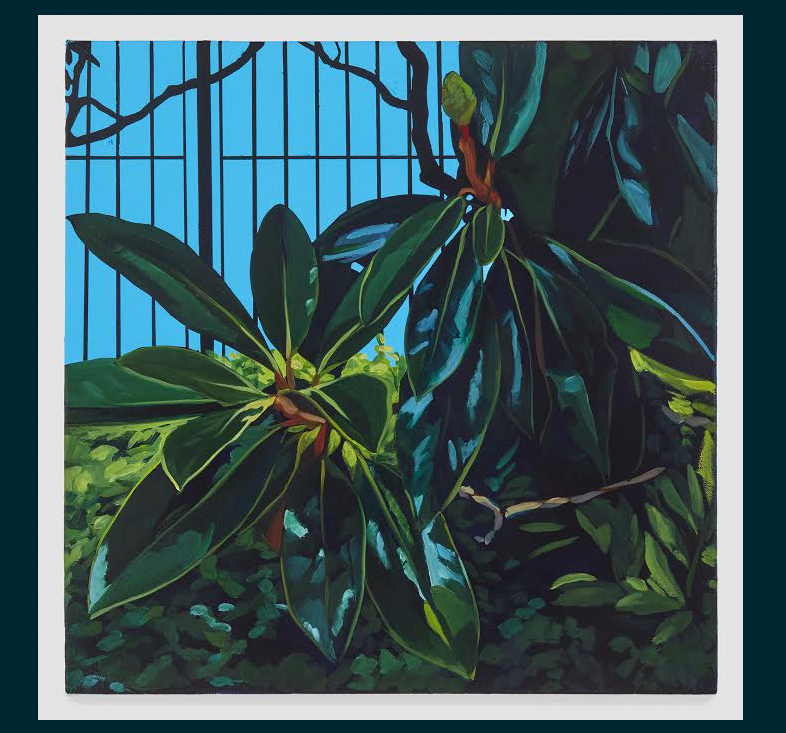

NB: What really struck me in your work, particularly the pieces where the figure is absent, in the “Blue Series”, the freshness of the greens and the brightness of the blues, but the figure is missing. It’s jarring because it’s so fresh and inviting, yet there’s this history through the absence of the figure or through the homes or the landscape that’s gives it a darkness the viewer internalizes. Even though the painting is so vibrant and stunning, the trauma is internalized in the viewer but not on the canvas. It’s very clever.

KB: It’s meant to be a “spoonful of sugar”. It’s beautiful, inviting, bright, happy. But naturally in a lot of people there’s an idea of incredulity. Something’s up, something’s missing.

NB: Are there any writers, poets, or artists you’re looking at right now in the studio?

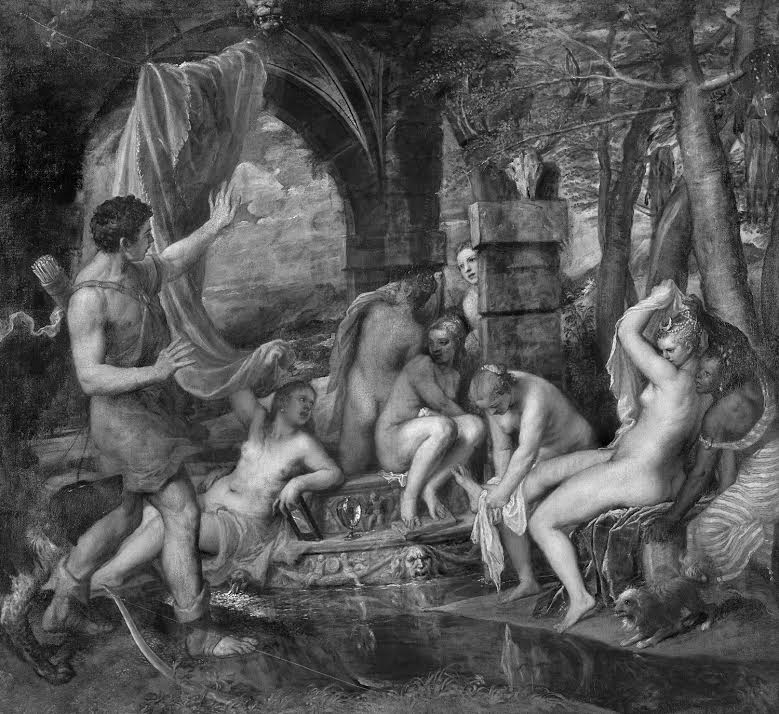

KB: Most definitely. I’ve actually been reading Dave Hickey’s first book, Invisible Dragon. He talks about how things should be beautiful. I felt that immensely when I went to Venice and visited the Galleria dell’Accademia to see the Tintoretto panels and Tiepolo ceiling paintings. It took me back. I was like “woah” this is inspiring. They’re from hundreds of years ago. From a time when people dedicated their entire lives – generations of lives – to making things beautiful. That’s a paramount goal in my work, I want to make beautiful paintings. It can still be beautiful and challenging.

NB: And it can still be dark!

KB: It can be dark! Again, spoonful of sugar. It helps you swallow some of the darker histories if they’re told in a beautiful way. At any rate I’m loving the book. The way he’s able to talk about how Caravaggio collapsed the space between the viewer and the painting. Even to look is to be involved with Doubting St. Thomas. To look is to doubt. The painting performs its ethos and message in its meaning. Some other artists – Hurvin Anderson, I’ve been looking at a lot. He won the Turner Prize a few years ago. Another person deeply invested in looking at background space and landscape to the point that he’s going over and over these spaces, redoing them, pulling them apart, reimagining them. And Patrick Caulfield, making these pretty paintings about composition and design in a very interesting sort of way. Other than that, I’m still reading Brothers of Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. I’ve been reading it for 7 years now. I’d gotten 500 pages in before grad school and put it down for a couple years, now I’m picking it back up. That’ll be a lifelong journey.

NB: Is there a body of work you’re focused on right now?

KB: I’m still fixated on the” Blue Series”. It hasn’t come to fruition the way I want it to. I want a complete show of these works. I have the title and I already know the organization, but I’m still working on building it up. Other than that, I’ve been working on a series of dark paintings, just playing around with how low of a value range I can work in. I think the two bodies sort of inform each other. In one you have the idea of the outdoors; the precarity and sublime of that outdoors tied to a radical blue sky, which is traditionally meant to connote safety, up against a series of works that are trying to convey intimacy and comfort in dark unseen spaces – which are traditionally meant to be scary or unsafe. It’s an inversion of traditional tropes of light in art history and culture. It’s not an wholly original thought: David Hammonds had that amazing piece where he blacked out an entire gallery and gave attendees flashlights that were impossible to use. To be seen is to be unsafe, and the safest point is in a corner in the dark where no one can see you.

NB: I think exploring the different levels of darkness in a series isn’t something you see all the time. Being able to find ways to interplay shades of darkness with some type of beautiful scene really plays against the notion we have in our minds that darkness is danger. I love how you’re exploring the binary of that darkness and light and how it plays on the viewer’s sense of safety and security and those traditional notions.

KB: I think also of the idea of wanting more, wanting to complete the picture with light. There’s a stoking of curiosity.

NB: And with that dark painting that you have, it invites the viewer to examine it closely to see how the shades are playing with each other to create that dimension. Do you want to talk about recent or upcoming shows?

KB: I was in a couple of interesting group shows towards the end of this year. “Voices” which was curated by Anwarii Musa had a really great collection of artists: Jeffrey Meris, Derrick Adams, Nate Lewis, my good friend Dominic Chambers. I was also in a smaller show in Brooklyn titled “American Socialist Realism” at Rumpelstiltskin gallery. I was shown alongside Martin Wong, Tseng Kwon Chi, Hannah La Follette Ryan and Clark Filio. I think the curators were asking interesting questions about figuration; placing realist figuration within the idea of propaganda. I think we can easily get locked into the idea of figuration/representation as an immediate celebration. Which isn’t always the case. You can represent terrible things. There’s various aspects of human life to represent. There are very important questions about who has traditionally been represented and a necessary redress of underrepresented bodies. But representation is complicated. Multiple poles can be brought into the idea of figuration.

NB: So you clearly have an inspirational story and I believe you’re destined for greatness. But what advice do you give to young artists? As a professor, what advice do you give to your students and to young artists figuring out if they should pursue a life as an artist?

KB: As an art professor, it’s funny how often this question comes up. I’ve had students come up and ask what they can do to become a successful artist. Sure take your work seriously, challenge yourself, but it really boils down to just not quitting. Don’t quit.

January 20, 2021

Creative Legacies

An Interview With Kathy Battista and Bryan Faller

NB: What are creative legacies and why is this field of expertise so important to study?

KB: A creative legacy is the sum total of what is left behind in any creative practitioner’s life and career. Most people think about work. Like when Rothko died, you think of all of the paintings that are left. It’s much more than just work, it’s things like an archive. So perhaps receipts, which tell us what kind of paints he bouhth would help with restoration. Or receipts that tell us who his framer was or who built the stretchers. This also includes letters from people. Bryan and I have worked with an artist for example who was quite close with Calder, but he’s much less known. So, letters between him and Calder or experiences like an oral history recorded with his children detailing Calder’s influence on him is part of understanding that artists’ work. It’s also things like real estate and money. Those things are also part of creative legacies because you have the tier of successful artists where they have more than one or more houses or apartments but then also some unsuccessful artists who were able to obtain real estate in the 70s when Soho was super cheap and now that’s worth a lot of money. They were able to sustain a radical art practice without having to be an A list artist, but that’s still left behind as part of their legacy. So all of these things have to be worked out, it’s not just the art. The legacy lives on in their family and in their studio assistants or managers that have a wealth of expertise in their own bodies and minds.

BF: I started working with artists and their estates and families 10 years ago. I was supporting Douglas Baxter in his office. We were working with Judd and Sol Lewitt. I had the privilege of learning with that level of studio practice. These were wealthier artists, wealthier estates. These are artists who have collections of other A list artists. When you’re dealing with significant artists critically and commercially, you can do a lot more. Like Nicole, your experience with Rauschenberg. You can do so many more things with money. You can have internships, you can have foundations, you can have separate businesses within the estate and foundation. The creative legacy is really about what we do with the resources that are left. The idea is to do this before the artist is dead. It’s a two-parter. This is a conversation the artist starts before their death, which continues after they die. It’s about the artist’s intentions. Really, it’s economic. How do we manage the remaining assets of this artist? Whether they are art assets, the body of work, the archive materials, or critical dialogue surrounding the artists. That’s the job of the gallerist. Who’s seeing this work, who’s working on this retrospective? Are we talking to MOMA? The Whitney? The Guggenheim? Pompidou? There’s a critical conversation that’s economic, and there’s an economic conversation that has nothing to do with the body of the estate. There’s two parts of an artist’s estate–the creative estate and the “stuff” left from a life that everyone has. They’re kept a bit separate, but at the end of the day the artist’s studio still has to deal with the body of work.

KB: What Bryan said about their own collection was very interesting because some artit’s also have collections of other artist’s work. It’s interesting to go into someone’s flat files and find a Robert Smithson drawing or a Peter Beard written on in a pile of papers in their desk drawers. Those are the kinds of discoveries that you make because artists are friends and swapping with other artists.

BF: You really start to see the influence then. This was another area of research that came out of this. You start to see studio practice being influenced by various elements other than strict art and art history. What are their gallerist friends saying to them? What are the other artists saying to them? What are their collector friends saying to them? How is all of this feedback coming in and re-influencing what they’re making? Sometimes they chose the color blue not because of something esoteric or ephemeral but because blue sells. You don’t know until you read a note someone wrote that this was a commercial choice that they made. Which is fine, it is what it is, but you have to know.

NB: I do feel like this field has been a relatively new point of interest for the art world. The realization that there needs to be more academic study and dedicated professionals to this area has developed mostly by seeing travesties with artists’ estates. The realization that there needed to be more structure and rigor to this portion of an artist’s life and beyond. There is such a lack of academic writing in this field. Where was the genesis of the book? What kind of gaps were you looking to fill?

BF: I was teaching at Sotheby’s and Kathy asked me to lecture with her in the Estates class. We were looking for readings and couldn’t find anything. I said kiddingly, we should write a book. Kathy turns to me, dead serious, “Darling, we have to do this”. I’m sitting there thinking we’re just pontificating, but it really started materializing.

KB: We were at my corner office at Sotheby’s. We knew Loretta Wuürtenberger’s book was coming out because Carl von Trot had gone to Sotheby’s, and we were in touch with him still. We were waiting for it to come out for the class. We thought of doing our own book. We proposed one to Lund Humphries since it has a relationship with Sotheby’s institute. They were keen on it. The timing was also good because the editor Lucy Meyers, who’s wonderful, was coming to New York two weeks later to talk about a possible book. It was very organic.

BF: It happened very quickly.

NB: Was the intention always to have contributors? What drove your thinking around the format of the book?

KB: It was the fact that we thought we could get different and disparate points of view like legal, archival, or curatorial from getting different people involved. For example, Bryan had the idea to get Alexandra Bowes-Lyon to write about English country-houses and the art in them which was fascinating because that whole structure changed so much in the 20th century. My knowledge was limited to Downton Abbey. We had a person whose family actually lived through it and knew it. That was great.

Then, you know, someone like Natalie Khan, who’s dealing with this quite a lot in fashion. She’s researching people like Leigh Bowery. The idea for us in getting different disciplines was that although there’s no one size fits all even for artists, you can make some structure, there’s something every estate should do, but each one is so unique. You can’t just take a blueprint and put any artist’s estate into it. There are always curveballs. What we thought too is, wow, this is so similar to a film director, architect, fashion designer, or jewelry designer’s estate. There are archives, the works, the oral history handed down in ateliers. We thought it would be interesting to extend the discussion to other disciplines. All of the books on estates so far have been focused on the visual arts.

BF: For me, a few things stood out. Just nuances. The contributor list changed. There’s a difference between practitioners and academics. It’s a different approach to what’s being discussed. That’s what we wanted. We wanted people with granular knowledge who were in the trenches and people who necessarily weren’t but had studied this. They were granular on a different level. Some contributors had to fall out because they didn’t know how to discuss it because it’s such a nascent thing. There isn’t a field of creative legacy practitioners. It’s people who deal with art in different capacities. I think a lot of people are dealing with creative legacies in their own ways. You don’t go to school to do this. You fall into it. Artists say “Hey, can you help me put together an estate plan.” Or “Hey, can you help me liquidate or sell or find a gallery.” Robin Wright, a jewelry specialist who’s a friend of mine at the auction house, was keen to write something with us. She gave us an image from Verdura, the jewelry house. Even Verdura was buying back pieces into their own collection. the image she chose was a work they had bought back into their own collection. It was an early broach. It was fascinating because the clearance sheet I received was signed by a member of the Vedura family. It was ironic because here we are talking about creative legacies and here we have a major jewelry house using this essay as a way of managing their creative legacy. This is a minor thing in how they view their estate, but it was still part of it. They’re artisans, but they’re not conceptual painters or performance artists. You can see the threads to Kathy’s points in the similarities between the modalities. What’s staggering is how different each situation is.

NB: I find it really fascinating when you see how the fashion houses or couture houses take their iconic pieces back into the archives. They realize how incredibly important it is to build up and document that archive through the years. For artists, they go into museums, but outside of the visual arts, where do those iconic pieces live? They can’t be in grandma’s dresser. To bring them back into the ateliers is a way of preserving their own history. Do you see this book as an intellectual resource or a handbook or something else?

KB: We were adamant that we didn’t want to make a handbook. First of all, the Würtenburger book is good at taking you through the different things that need to be done and giving you a time estimate on it. There’s also a book by an artist widow that is sort of like a handbook. Then there is the Handbook For Artist’s Estates that is kind of old now. We didn’t want to do a handbook. We wanted to do something where people could have more freedom to talk about intellectual problems or issues that come up. Like where Mark Morris talks about architectural models and how they are so useful for pedagogical reasons, or the way Tom McNulty writes about appraising libraries or archives. We wanted to give people leeway to write on what they found interesting about legacies. Everyone has their own personal experience with it. Ann-Marie Richard had amazing experiences with celebrity estates, a lot of it that she’s not allowed to talk about. As a footnote to this, it was very interesting to see how estates and foundations are careful about how people write and talk about the work. It is an increasing trend that they want to see everything that’s written by a scholar.

BF: Just the process really taught us a lot about what people are willing to say, what they are not willing to say, which in some cases is understandable. People are just so unsure about how things are going to affect their artist or estate.

NB: How do you see the field of legacy planning expanding into the future?

BF: We talked about this a bit with Loretta Würtenburger when we interviewed her two or three years ago. We were at Art Basel and we happened to meet up. It was serendipitous. There are a lot more students too who are saying that they want to be a legacy planner. I didn’t know that was a thing. I’m like, yeah, you need to go to law school. Or you need to get into investment, which has nothing to do with art and artists’ legacies but then you can work with that. It was interesting just to hear where people are coming from. I think there should be an educational opportunity for a certificate that guides you through the issues at hand. At the end of the day, if you’re an artist’s legacy practitioner, you need to be the quarterback. Or studio manager. You need to come in and be the person who is taking everything into account. Managing the financial advisor, the lawyer, the studio, the family.

NB: And you’re applying the art world knowledge and practices across all of them.

KB: I think what we’re seeing now are more agencies developing to deal with artist’s estates. I think we saw this with Sotheby’s when they went into this. It’s such a boutique industry. Each estate takes so much work and so much finesse, it’s almost better for independent practitioners. For the people who are artists and artist’s families to see the role of the artist advisor to shepherd estates too. It’s very hard to take on ten estates for any company. I think most of these places have a few artists that they maintain very well. I think Sotheby’s plan was to have 12 artists at a time. I think it’s unbelievable how much finessing there is with each estate.

BF: At the end of the day, these are really emotional situations. Whether we’re selling works from a private collection or creating an estate plan, you have intimate knowledge of people’s lives.

NB: It’s not always the conversation that people want to have prior to their death. It’s a difficult topic for an individual and their family members to have to face.

BF: Especially artists. Artists want to live forever, and in a way, their work will.

December 21, 2020

Must See Exhibition

Derek Fordjour:

“Self Must Die”

Derek Fordjour’s paintings, notable for their layered textures and materials, address complex themes of race, inequality and American society. Fordjour has achieved astonishing commercial success and firmly cemented his place in the art world. At Frieze art fair in 2019, he sold 10 paintings to Jay-Z and Beyonce. He often depicts Black athletes and performers–dancers, riders, rowers, drum-majors–characters that “navigate the ambiguities that come with their achievement, and the racial scrutiny that accompanies visibility in the mainstream culture.” With his newer work, however, less emphasis has been placed on these performative roles, and more on memorializing Black lives lost this year.

He explores mourning in a new ensemble painting “Chorus of Maternal Grief”, creating specific portraits of women like Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett Till’s mother, Tamika Palmer, and Breonna Taylor’s mother. In “Pallbearers”, he features the coffin of George Floyd. The works are on view alongside other installations, including a puppet show, at Petzel Gallery in “Self Must Die”. Accompanying Fordjour’s show is an epigraph from “In the Wake: On Blackness and Being” written by scholar Christina Sharpe. Sharpe writes “What does it look like, entail and mean to attend to, care for, comfort, and defend those already dead, those dying, and those living lives consigned to the possibility of always-imminent death, life lived in the presence of death… it means work.” Sharpe refers to “wake work”, an “ensemble of activities, grand and mundane, that acknowledge and address Black death, and in doing so, affirm Black life”. Fordjour addresses this concept alongside Black liberation theory and studies of Black mourning within his new work.

December 14, 2020

Artist to Watch:

Chiffon Thomas

Memory and Materiality

N: Can you tell us your story up until you were accepted into the Yale program?

C: I’ll start with a story about my high school experience because it’s how I got into embroidery, which is always featured in my practice. I was a senior in high school when I first took art. I had a teacher who would bounce ideas off of me. One day, she showed me a book on this artist, Daryl Morrison, an embroiderer who embroidered narratives about his upbringing. He wouldn’t use image references to create them; they were more imagined and illustrative. She asked me what I’d think about assigning a project like that for the class and having each student bring in a photograph to embroider. That’s how this journey started: I brought in a photograph and was able to embroider it. I was able to do it really quickly and she assigned me to do an entire portfolio of 12 of them. I ended up applying to the Art Institute with that work. It all happened so quickly. I was accepted into the Art Institute and actually studied education instead of art. I wanted to be a teacher and create an impact on someone’s life. I ended up getting my Bachelor’s of Arts Education, so I started teaching in Chicago public schools for 3 years. I taught art full time. It was a nice experience for me, but I didn’t have a lot of time to be in the studio or a practicing artist. It’s something I always had a desire to do. I always had these creative projects and ideas for my students that came from my own interests and wanting to make art myself. I ended up leaving teaching, just to have the opportunity to express and create a body of work. For a year, I didn’t have a job. I worked in the basement creating a portfolio to apply to grad schools to study art specifically and get a master’s. I made this portfolio from 2017-2018 and ended up applying to seven different universities and grad programs. I got into all of them except for one. I went to Skowhegan using the same portfolio. It was so crazy because I didn’t have a lot of exposure to art. I was mainly focusing on education and psychology—so I didn’t get a lot of that background. When I went to Skowhegan, it prepped me for being in a program like Yale. It exposed me to readings and artists that I was super unfamiliar with that actually helped to inform my practice when I started grad school at Yale.

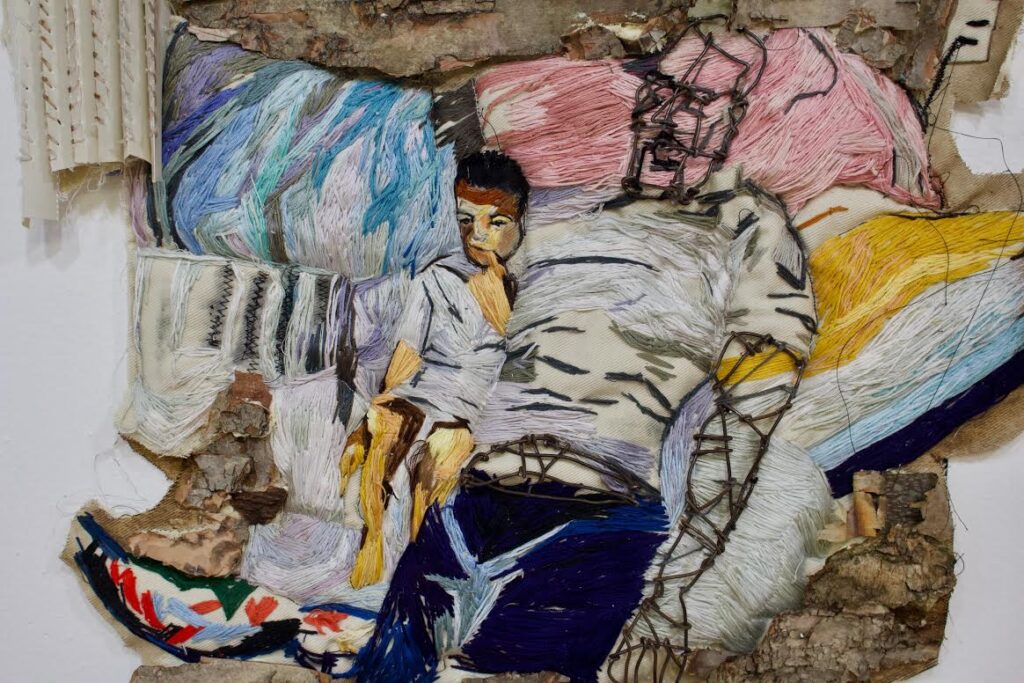

N: Why don’t we talk about some of the themes you explore in your work and how has your journey contributed to this? How do the various materials contribute to the idea?

C: I guess I’ll start at the beginning, around the time I was creating these bodies of work. I came from the interest of working with family photographs. I continued that because I look at family photo albums all the time. I know a lot of people do because it’s different from looking at a digital device. It’s so nice to have something tangible. Something shot in film is so different from being shot on your phone. I look at family photo albums out of pure nostalgia and a desire to be seen as an individual that can aspire to be anything that they want to be. As I was growing into adulthood, some of the ways that I wanted to identify were not accepted or rejected. The pull and distance created in my relationships with my family were making me self-aware of not having a space of belonging. I was craving to have those things I would find in family photo albums and to investigate where they were or where they got lost over the course of time. I started to recreate them in these large-scale embroideries, which I was making in 2017. Everybody loves to look back at their pasts and at their family. Giving people access into Black family structure was something I didn’t realize I was doing at the time. When viewers would actually engage with the work, I could tell they were looking at a world they didn’t have access to before. Even crafting these domestic scenes out of fibers, using things like pillowcases, brought things home to people. They saw how familial bonds were created through families like mine with the tenderness of these relationships and how fragile they are. A fragility is presented in the bodies that aren’t represented as well. People have a level of care and can relate to those images that I make of my family. That’s what that work was about. Even now, some of those things are finding their way into the bodies I make even when I’m not directly showing something that’s pictorial in my work. People can see the humanity—I want the humanity to be present in the work in the way that I’m handling the body. There’s this reconstruction of a being from being constantly oppressed, beat down, misrepresented or projected upon in these misinformed ways. I try to correct this and shift the viewer’s eyes and show a psychological perspective. I bring that through material too, as material has its own history or it’s weathered or not polished. You can see its scarring and how those things occurred through its activities without you being present. You end up finding ways to repurpose it and reconstruct back into a form where it’s not devalued.

N: Allowing the material to almost live like your skin, because your skin is scarred and has bruises and marks. It’s a living organism like the materials you used. When you mentioned your embroidery, pillowcases, fragility and tenderness that comes with that, all I could think about is the smell of someone’s pillowcases. When you put your head down on that pillow and get that “ah, this is my bed” it conjures the nostalgia and comfort of your home, and how you grew up. It’s a beautiful way to look at these things.

C: It’s so crazy how our senses are activated from something we remember. I was watching a TV show I hadn’t seen in years. Over the summer, I just said “Let me find it on Hulu.” I rented it and was watching it in my room in the dark. Immediately, I felt immersed in a setting or time period where I used to watch the show all the time. It overwhelmed my whole experience. I felt like I was back at that age in the room I was watching it in. I hadn’t felt something so intense. I felt so nostalgic.

N: It’s an intangible feeling. Let’s talk a little bit about the last year. I know you were recently featured in the show and subsequent catalogue “Young, Gifted, and Black” with Bernard Lumpkin. You have some extraordinarily talented friends, some that are friends of mine. Who do you look at in the generation before you for inspiration and admiration?

C: I know that that book is going to make an impact on artists. It’s so crazy to even think about. The work in that book is so strong and experimental. Bernard’s collection has a nice, rich variety. It’s such a genius idea. For that work in particular, I was looking at a lot of popular culture. But for composition and color I was looking at this court case illustrator. This woman illustrated the Cosby trials, Christine Cornell. The way that she composes her court case scene are like a scale of individuals enlarged to show exaggeration or give weight to the actual mood occurring with her ability to use color. She did a lot of drawing with chalk pastels. That’s how I translate images: I translate them into pastel drawings. I got that from looking at her drawings. That’s a nice approach to understand color, human anatomy, and muscles. I was really learning from the way that she composed mood. I also sometimes just look at things that pop up on social media or even googling certain words and seeing what images I link to those words in search engines. I get a lot of inspiration from that. Another artist I was looking at was Lauren DiCioccio, a soft sculpture artist that embroiders The New York Times in painterly, fluid ways, allowing the thread to hang freely. She wasn’t just doing that, she was making soft sculptures of things like polaroids, shopping bags recreated out of fabric and fiber. I just thought that was a way to kind of elevate and archive a moment in your history. It is mundane, minute, or overlooked, but you have taken the time to care for this object and give it a sense of importance. I really liked her aesthetic and tried to incorporate some of those techniques into my own practice. I was also looking at Sedrick Huckabee, who is also Yale alumni. He painted these little paintings of domestic spaces that pulled the eyes in dramatic ways, like the foreshortening of an image or a perspective pushed back. He has these images of his grandmother in a bedroom scene that are really painterly. The paintings have a kinetic appeal to them, even though there in the mixed format of paint or whatever material the artist is exploring.

N: Can you tell us about your most recent shows and residencies, and what’s coming up?

C: I’m in a group show in Beacon New York, “Parts and Labor”. I was just in the group show “Myself” at Kohn Gallery in LA, which ended this month. I’m going to be in my own solo show at Kohn Gallery in March. I recently finished Fountainhead Residency. I was there for a month and it was amazing. It was in Miami. Kathryn Mikesell and Dan Mikesell are amazing, they run the residency space. I’m going to be in Art Basel and I’m showing work with P.P.O.W. in New York. I’m showing an embroidery and three drawings. I’m also going to be represented by P.P.O.W. and Kohn. Plus, I have some exciting things coming up in the new year. Lots to look forward to!

November 24, 2020

The 2020 Art Market

The art world is experiencing a necessary evolution and expansion in 2020. Nothing replaces the experience of standing in front of an artwork, feeling its aura, and hearing its story, yet the art world has been thrust into the world of digital viewing rooms, online sales, and price transparency like never before. While shut down, galleries and auction houses found new ways to stay connected to collectors by staging virtual exhibitions, developing content, and hosting Zoom panels, initiatives that galleries had on the back burner for years. The upside: viewing art is made more accessible through virtual options and price transparency has been embraced. Buying art online is not a new concept; Gagosian sold a Cecily Brown online for $5.5M in 2019. Yet, it has generally been a resisted concept until becoming a necessity.

This time last year, we would have attended dozens of art fairs across the globe, riding the endless merry-go-round of fair-after-fair. Now, almost all fairs have now paused and (many of us) have taken a collective breath. Dealers, galleries, advisors, and auction house specialists have had to lean into the digital and figure out how to translate the storytelling of artworks online, followed up by an old-fashioned phone call and emails. What we have found is that privately existing collectors make up three-quarters of online sales and are comfortable transacting into low six-figures online. However, the auction houses tell a different online story and have seen multiple seven figure bids and sales, including an online bidder from Asia for a Francis Bacon that sold at Sotheby’s for $84.5M in June 2020. In this same Sotheby’s sale (the first since lock down), the art market took a giant sigh of relief when it totaled $300 million USD, signaling that collectors still had a heartbeat. High net worth collectors have demonstrated that they’re still comfortable buying at $250,000+. It wasn’t until the cliff of the election that we started to see jitters at $4M+.

Beyond the shift to digital, collectors have continued to demonstrate a keen interest in collecting cross-category, which is not surprising, unless it’s a dinosaur. In October, Christie’s placed STAN, the largest and most complete fossil ever found of a T-Rex in their Evening Sale, alongside Picassos and Pollocks. It sold for $30.8M against an estimate of $6-8M. Similarly, Sotheby’s placed three Alfa Romeo’s, an automotive triptych from 1953, 1954, and 1955 that resemble something from The Jetsons, in their Evening Sale, fetching $14.8M. Just as Lizzo described herself to Letterman, collectors are multi-faceted. They love beautiful things that move them and tell a story regardless of designated genre.

While the highest echelons of the market are buzzing, it’s important to recognize young talent, especially MFA students who graduated this year. There are so many gifted artists out there and it will be my pleasure to share the work of Hangama Amiri in the next artREAL article. Stay tuned!

November 9, 2020

Artist to Watch:

Hangama Amiri:

Storytelling Through Textiles

N: Can you tell us your story up until you were accepted into the Yale MFA Program?

H: I was born in a refugee camp in Peshawar, Pakistan in 1989. That was during the civil war, the war in Afghanistan, where people were migrating from country to country. My Mom was a refugee in her own neighborhood. I spent most of my life in Kabul, Afghanistan, and that’s why I call myself an Afghan artist. Since then, when the Taliban took power in 1996, we became refugees to Pakistan again. We were there until 1999. After that we became refugees to Dushanbe, Tajikistan. We lived there until 2005, when we immigrated to Canada. During these times I was always interested in the arts. From a young age I was always drawing my dreams and stories about moving country to country. I was also drawing about my future or my utopic hope for the future. It was really interesting. In Tajikistan I took my arts seriously, because I won a small scholarship in the arts program. It was a two-year scholarship for the Olimov College of the Arts. I applied through a UNICEF competition–I won first place and that led me to a two-year degree in the college of arts. From there I learned a lot about academic drawing. It was a very Russian based school, so they taught me a lot about observational life drawing. My passion for that grew, and when we immigrated to Canada in 2005, I decided to continue making my art. I graduated my BFA program from NSCAD University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. From there I took five years to exclusively do artist residencies. I’ve done residencies in Europe and Canada. I was also a Canadian Fulbright. I completed an independent research program at Yale University—it was a different program at than the MFA, but being in New Haven for a year as a Fulbrighter gave me an opportunity to be closer to the Yale School of Art. There I made really close friends. Tomashi Jackson was still in school, it was her second year I think. Alteronce Gumby was there too, so lots of great artists that we now know these days. It was really interesting because people were so serious about their art and their views in artmaking, practice, and material. Discussions were taking place and it really opened me to also seeing my art here someday, at this level. I took another year off again after my research and came back. I graduated during the pandemic, and now I’m still working and living in New Haven.

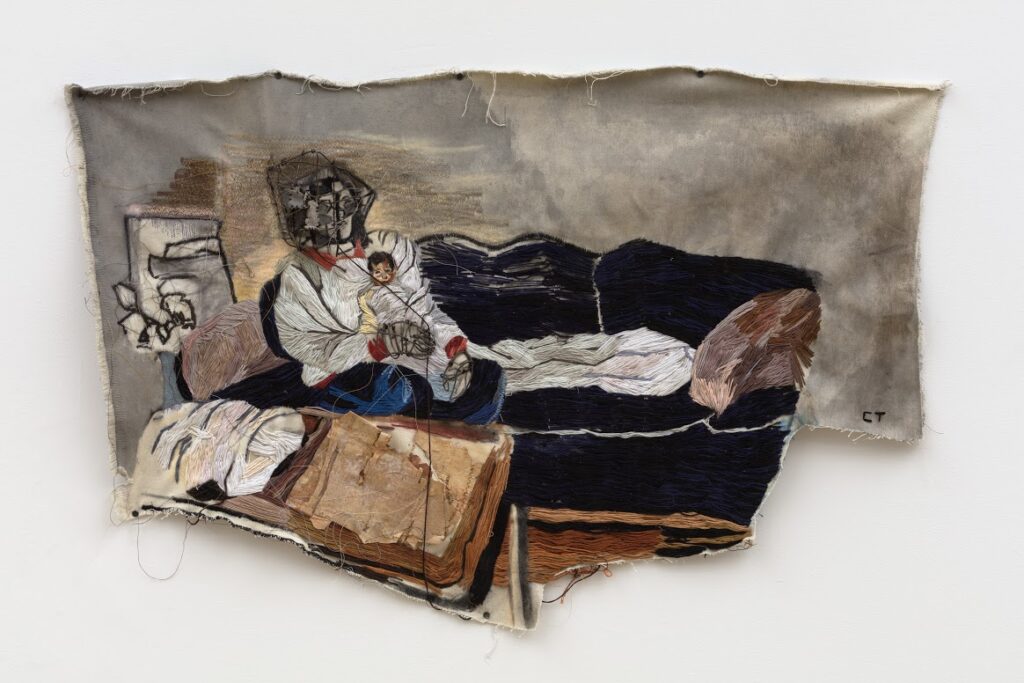

N: What themes do you explore in your work? What does your creative process entail? How do you explain your choice of medium?

H: In my art practice I explore themes of childhood memories, fragmented identities, gender, and the contemporary Afghan women’s voice. These themes have always been my interests, for a long time—painting the untold stories of the Afghan woman and bringing them into the visual arts context and giving them an importance and voice.

My process really takes place in the beginning when I start making my projects. I do a lot of looking into the visual culture specifically in Afghanistan. I research and draw a lot. I also sketch out my plans and the direction the theme will take. From there I go on to fabric. In the actual material process there is a lot of fabric appliqué, cutting, and collaging involved. There is a lot of painting with gouache, colored pencil, or colored markers to give me an idea of color as a memory and how I memorize those colors. That’s my process—juggling materials before the actual finishing of a piece.

The medium of my choice is textile. I call them “textile art” pieces because the fabrics that I’m using aren’t just fabrics in shopping malls or in fabric stores, but they are geographically specific. They’re not only from the garment district of New York City, but from Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Tajikistan. It’s really important for me to choose my fabrics specifically based on their context and culture.

N: Where did you learn how to sew?

H: I learned sewing on my own at Yale University. I started at Yale as a painter, but I slowly became interested in collaging. My paintings usually evolved around painting cultural patterns from memory that related to Afghan culture or how women would dress in certain patterns or fabrics. So I was interested in painting fabrics, but from there I questioned the material a lot. I was having problems with canvases too. Slowly, I gathered materials together and started stitching them and uniting them. I started needling first and that became such a meditative practice in my studio. I was really looking forward to stitching, uniting stories together. From there the machine made it a bit faster, gathering materials quickly to embroider. It became a drawing tool for me and now I make my own patterns using the machine. I was inspired by my school–I wasn’t the only artist working with embroidery. My group was so diverse in their craft and materials. Together we were all learning about this history of fabric and embroidery. So, it was a really creative year.

N: Why don’t you tell us about your MFA work Beauty Parlor and some of its elements and meanings?

H: I did the Beauty Parlor series when I was in my second year at Yale. I really focused on women’s issues again and women’s social life in Kabul city. I was thinking of my recent visits back there and how my relationships were with the community of women. The society is very gender constructed, so I had most contact with my own cousins, my own women. So, it was really interesting for me to wherever I explored, be surrounded by women. Salons are really interesting because there were so many women’s salons in Kabul. It really inspired me to see women in business that created public spaces where they could go, do makeup, be beautiful, treat themselves, you know? It was really beautiful to go there and be with them, because a few of my cousins also had weddings. It was really celebratory to be around them. In this piece I was very interested in the spaces that women shared. In that particular series I depict women being treated. There’s a bride sitting in the center of the piece that’s also gazing at us, while the other person is treating her hands. It is such an intimate space as well, because there are women to women treating each other but no other contacts. On the right side you can see women waiting in a waiting room. The top part is the title of the Shop. It’s called Arayeshgahe, Bahar in Farsi. And on the left side we have a soldier standing with the sign of a gun. Mostly, when women from important families would visit these public spaces, they would always bring a guard with them, just for security. So, no matter how free they would feel inside, outside was still a war-zone. They would feel insecure being outside, so I wanted to reference that part as well. In this piece the fabrics that I’ve used, in this piece specifically, have traditional Afghan coatings in cut-out and collage. It also shows a dollar bill, because people were using dollar bills in a state of Afghan money. It was interesting to see there because I still felt like I was in America or in Canada instead of Afghanistan. That object was really familiar to me. In this piece I also use photographs that are references to Bollywood actresses or movies, because those salons also had a lot of posters of Western models or Indian, Bollywood actresses. That also references our talk about beauty politics. Questioning the beauty politics of Western culture, me being here for example, is about appearance. But there, the beauty politics are very much within themselves. As soon as women walk outside, they wear a veil. They want to be beautiful within their own communities. So, it is also a question of those layers that I played with in this piece.

N: Tell us about your most recent shows. What can we expect from your shows coming up?

H: A few of my recent shows were online, with everything moving to the online platform these days. A recent one that I was very happy about was with Perrotin Gallery, where they invited a group of artists from the MFA program to show our Post-Thesis shows on online platform. That was very successful and we were very happy to be still involved in the arts scene after graduating.

I am really excited about my solo show with T293 Gallery in Rome starting November 21st. The title of the exhibition is called “Bazaar: A Recollection of Home”. It’s pretty much reminiscing a bazaar environment in fabric, and this environment comes from my childhood memories of growing up in the bazaar. I’m pretty much transforming this space with the things that I’ve seen in the bazaar. The objects that I’ve seen are the objects that I relate to, specifically because when I was young, I always used to go to the bazaar with my aunts and with my Mom. We also used to go to the tailor shop and many clothing stores. Again, beauty salons, nails salons. So, these were the spaces where women would spend their leisure time on Friday or the weekends. Remembering back, that space tells a lot about time, politics, and history. Back then it was pre-Taliban and I could still witness that there weren’t many businesses owned by women. It was still a very male-dominated public space. Comparing that to my recent visits to bazaars, it actually has changed. I’ve seen so much hope in the voices of women. This space has transformed, and these women attract more women, business-women. They have beauty salons under their names. So for me, in this solo exhibition, I’m creating a space that women feel they belong to, which is the bazaar. The bazaar is a space in Post-Taliban society that women still don’t feel that they belong, a part of the public space. But for me in this exhibition, I’m creating an environment where women are the most important thing, with their voices, images, and names being written loudly.

N: In the current climate of political divisiveness, cultural reckoning, and social justice, what do you believe the role of the artist is at this moment in time?

H: I really love this question, Nicole. I think it is a very tough question, but very important for artists to have. All I can say in this situation is that for me, it’s everyday. For me the role of an artist is to never stop working, never be silent, and also never fear. It reminds me of a really good quote by Toni Morrison: “This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That’s how civilizations heal.” I feel like her quote is so important to always look back on in these political times we live in. She says it all.

N: So, keep working?

H: Yes, keep working. I think we have the tools to challenge the facades that are happening in our daily life.

N: Well you beautifully place the strength and power of Afghan women, central within your work. You’re doing this everyday. Thank you.

H: Thank you, I appreciate it. No stop sign yet!