December 14, 2020

Artist to Watch:

Chiffon Thomas

Memory and Materiality

N: Can you tell us your story up until you were accepted into the Yale program?

C: I’ll start with a story about my high school experience because it’s how I got into embroidery, which is always featured in my practice. I was a senior in high school when I first took art. I had a teacher who would bounce ideas off of me. One day, she showed me a book on this artist, Daryl Morrison, an embroiderer who embroidered narratives about his upbringing. He wouldn’t use image references to create them; they were more imagined and illustrative. She asked me what I’d think about assigning a project like that for the class and having each student bring in a photograph to embroider. That’s how this journey started: I brought in a photograph and was able to embroider it. I was able to do it really quickly and she assigned me to do an entire portfolio of 12 of them. I ended up applying to the Art Institute with that work. It all happened so quickly. I was accepted into the Art Institute and actually studied education instead of art. I wanted to be a teacher and create an impact on someone’s life. I ended up getting my Bachelor’s of Arts Education, so I started teaching in Chicago public schools for 3 years. I taught art full time. It was a nice experience for me, but I didn’t have a lot of time to be in the studio or a practicing artist. It’s something I always had a desire to do. I always had these creative projects and ideas for my students that came from my own interests and wanting to make art myself. I ended up leaving teaching, just to have the opportunity to express and create a body of work. For a year, I didn’t have a job. I worked in the basement creating a portfolio to apply to grad schools to study art specifically and get a master’s. I made this portfolio from 2017-2018 and ended up applying to seven different universities and grad programs. I got into all of them except for one. I went to Skowhegan using the same portfolio. It was so crazy because I didn’t have a lot of exposure to art. I was mainly focusing on education and psychology—so I didn’t get a lot of that background. When I went to Skowhegan, it prepped me for being in a program like Yale. It exposed me to readings and artists that I was super unfamiliar with that actually helped to inform my practice when I started grad school at Yale.

N: Why don’t we talk about some of the themes you explore in your work and how has your journey contributed to this? How do the various materials contribute to the idea?

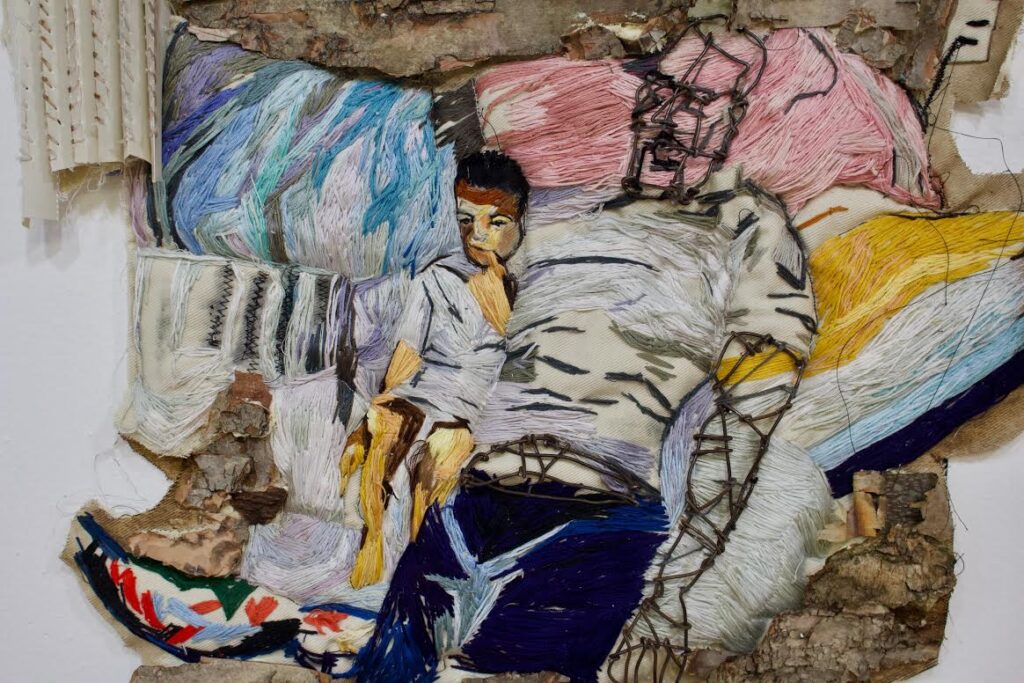

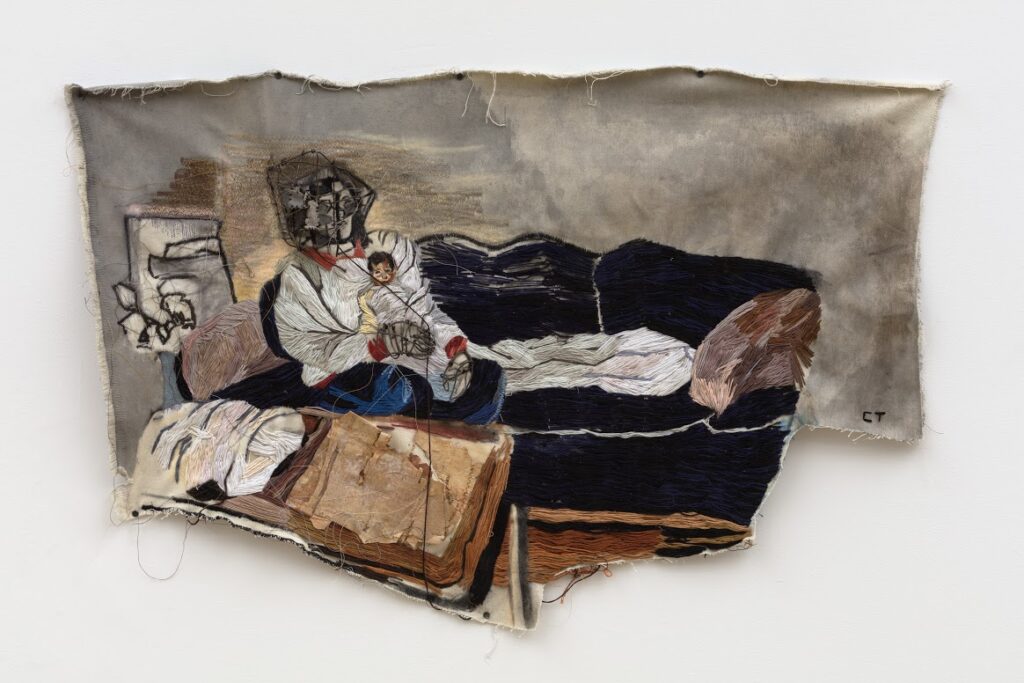

C: I guess I’ll start at the beginning, around the time I was creating these bodies of work. I came from the interest of working with family photographs. I continued that because I look at family photo albums all the time. I know a lot of people do because it’s different from looking at a digital device. It’s so nice to have something tangible. Something shot in film is so different from being shot on your phone. I look at family photo albums out of pure nostalgia and a desire to be seen as an individual that can aspire to be anything that they want to be. As I was growing into adulthood, some of the ways that I wanted to identify were not accepted or rejected. The pull and distance created in my relationships with my family were making me self-aware of not having a space of belonging. I was craving to have those things I would find in family photo albums and to investigate where they were or where they got lost over the course of time. I started to recreate them in these large-scale embroideries, which I was making in 2017. Everybody loves to look back at their pasts and at their family. Giving people access into Black family structure was something I didn’t realize I was doing at the time. When viewers would actually engage with the work, I could tell they were looking at a world they didn’t have access to before. Even crafting these domestic scenes out of fibers, using things like pillowcases, brought things home to people. They saw how familial bonds were created through families like mine with the tenderness of these relationships and how fragile they are. A fragility is presented in the bodies that aren’t represented as well. People have a level of care and can relate to those images that I make of my family. That’s what that work was about. Even now, some of those things are finding their way into the bodies I make even when I’m not directly showing something that’s pictorial in my work. People can see the humanity—I want the humanity to be present in the work in the way that I’m handling the body. There’s this reconstruction of a being from being constantly oppressed, beat down, misrepresented or projected upon in these misinformed ways. I try to correct this and shift the viewer’s eyes and show a psychological perspective. I bring that through material too, as material has its own history or it’s weathered or not polished. You can see its scarring and how those things occurred through its activities without you being present. You end up finding ways to repurpose it and reconstruct back into a form where it’s not devalued.

N: Allowing the material to almost live like your skin, because your skin is scarred and has bruises and marks. It’s a living organism like the materials you used. When you mentioned your embroidery, pillowcases, fragility and tenderness that comes with that, all I could think about is the smell of someone’s pillowcases. When you put your head down on that pillow and get that “ah, this is my bed” it conjures the nostalgia and comfort of your home, and how you grew up. It’s a beautiful way to look at these things.

C: It’s so crazy how our senses are activated from something we remember. I was watching a TV show I hadn’t seen in years. Over the summer, I just said “Let me find it on Hulu.” I rented it and was watching it in my room in the dark. Immediately, I felt immersed in a setting or time period where I used to watch the show all the time. It overwhelmed my whole experience. I felt like I was back at that age in the room I was watching it in. I hadn’t felt something so intense. I felt so nostalgic.

N: It’s an intangible feeling. Let’s talk a little bit about the last year. I know you were recently featured in the show and subsequent catalogue “Young, Gifted, and Black” with Bernard Lumpkin. You have some extraordinarily talented friends, some that are friends of mine. Who do you look at in the generation before you for inspiration and admiration?

C: I know that that book is going to make an impact on artists. It’s so crazy to even think about. The work in that book is so strong and experimental. Bernard’s collection has a nice, rich variety. It’s such a genius idea. For that work in particular, I was looking at a lot of popular culture. But for composition and color I was looking at this court case illustrator. This woman illustrated the Cosby trials, Christine Cornell. The way that she composes her court case scene are like a scale of individuals enlarged to show exaggeration or give weight to the actual mood occurring with her ability to use color. She did a lot of drawing with chalk pastels. That’s how I translate images: I translate them into pastel drawings. I got that from looking at her drawings. That’s a nice approach to understand color, human anatomy, and muscles. I was really learning from the way that she composed mood. I also sometimes just look at things that pop up on social media or even googling certain words and seeing what images I link to those words in search engines. I get a lot of inspiration from that. Another artist I was looking at was Lauren DiCioccio, a soft sculpture artist that embroiders The New York Times in painterly, fluid ways, allowing the thread to hang freely. She wasn’t just doing that, she was making soft sculptures of things like polaroids, shopping bags recreated out of fabric and fiber. I just thought that was a way to kind of elevate and archive a moment in your history. It is mundane, minute, or overlooked, but you have taken the time to care for this object and give it a sense of importance. I really liked her aesthetic and tried to incorporate some of those techniques into my own practice. I was also looking at Sedrick Huckabee, who is also Yale alumni. He painted these little paintings of domestic spaces that pulled the eyes in dramatic ways, like the foreshortening of an image or a perspective pushed back. He has these images of his grandmother in a bedroom scene that are really painterly. The paintings have a kinetic appeal to them, even though there in the mixed format of paint or whatever material the artist is exploring.

N: Can you tell us about your most recent shows and residencies, and what’s coming up?

C: I’m in a group show in Beacon New York, “Parts and Labor”. I was just in the group show “Myself” at Kohn Gallery in LA, which ended this month. I’m going to be in my own solo show at Kohn Gallery in March. I recently finished Fountainhead Residency. I was there for a month and it was amazing. It was in Miami. Kathryn Mikesell and Dan Mikesell are amazing, they run the residency space. I’m going to be in Art Basel and I’m showing work with P.P.O.W. in New York. I’m showing an embroidery and three drawings. I’m also going to be represented by P.P.O.W. and Kohn. Plus, I have some exciting things coming up in the new year. Lots to look forward to!