February 16, 2021

Artist to Watch

Kevin Brisco:

Kevin Brisco:

Beauty and Absence

NB: Why don’t you tell us about your story up until you were accepted into the Yale MFA Program?

KB: I was born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, same house 18 years. I grew up in a very religious household, Seventh-day Adventist and Baptist. So I would go to church twice every weekend. From there I ended up going to undergrad in Connecticut at Wesleyan University. I was originally studying Political Science and Arabic and was convinced I would be a Foreign Service Officer. Low and behold I ended up taking art courses and found my passion. This is where I was willing to stay up all night to get the work done. From there I moved to New Orleans, where I worked in the film industry as a lighting technician. It was a wonderful gig, where you’re on set for a couple months and you have enough money for the year, so I could keep painting. I really enjoyed it in Louisiana. I was showing and receiving attention for my work. I had the feeling that “Ok, this could be a successful career.” However I felt that there were still a lot of gaps in my knowledge. There’s the things you know you don’t know and then on top of that there are the things you don’t even know you don’t know. I figured it was as good a time as any to reapply to grad school. It was my second time applying. I applied to Yale after undergrad and was waitlisted after a difficult interview experience. The second time I interviewed and had a much more generative experience. In the span of a 30 minute interview the two professors asked questions about my work that I had never considered. Finally I was excited at the possibility of attending because here was a place that I could undoubtedly learn some things I didn’t know I didn’t know.

NB: What types of themes do you explore in your work? How has your journey of growing up in the South, going to school in Connecticut, and working in New Orleans contributed to your practice in the last two years?

KB: In the most simple sense, I’m interested in figure-ground relationships. Particularly the background of the South, the American U.S., and how written into the landscape is the history and narrative of the figures occupying it. It allows the space of imagination within the landscape. You aren’t immediately given the histories of the traumas but you can sort of see the history or legacy of it through the shadows. Light and shadow are also an important theme, and the conception around light being historically seen as knowledge, safety, and awe-inspiring. I’m interested in the idea that difficult things can still happen in broad day-light. Questions of joy and trauma are all wrapped into one. I think its Saidiya Hartman, a Wesleyan and Yale alum, she was talking about how she wasn’t interested in displaying outright trauma but rather the spaces where celebration and tragedy are so intertwined you can hardly separate them. I’m interested in this idea of light as both a harbinger of safety but at the same time, light casts shadows. You can’t have shadows without light. Light is intrinsically tied to falling out of view or being hidden.

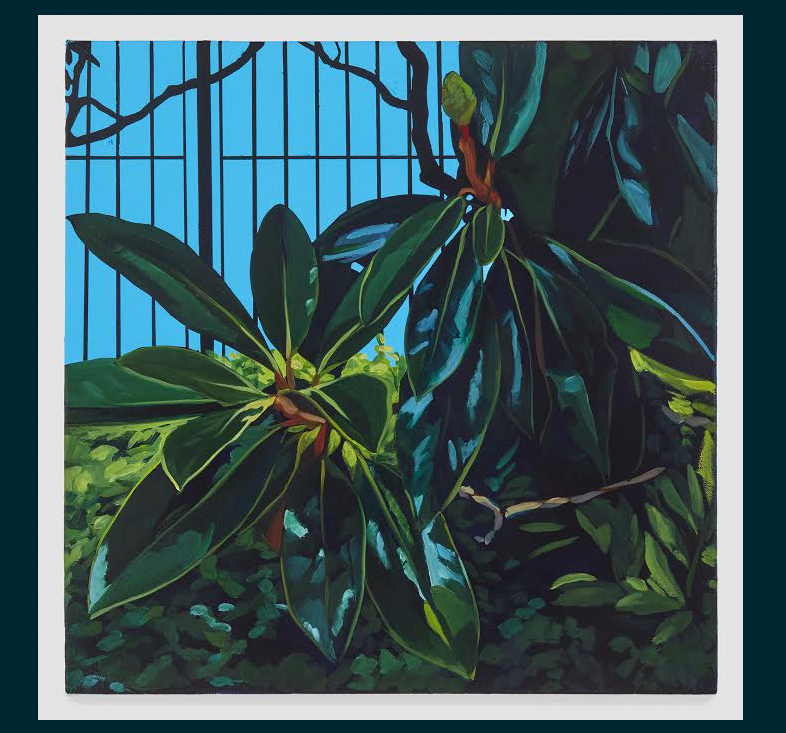

NB: What really struck me in your work, particularly the pieces where the figure is absent, in the “Blue Series”, the freshness of the greens and the brightness of the blues, but the figure is missing. It’s jarring because it’s so fresh and inviting, yet there’s this history through the absence of the figure or through the homes or the landscape that’s gives it a darkness the viewer internalizes. Even though the painting is so vibrant and stunning, the trauma is internalized in the viewer but not on the canvas. It’s very clever.

KB: It’s meant to be a “spoonful of sugar”. It’s beautiful, inviting, bright, happy. But naturally in a lot of people there’s an idea of incredulity. Something’s up, something’s missing.

NB: Are there any writers, poets, or artists you’re looking at right now in the studio?

KB: Most definitely. I’ve actually been reading Dave Hickey’s first book, Invisible Dragon. He talks about how things should be beautiful. I felt that immensely when I went to Venice and visited the Galleria dell’Accademia to see the Tintoretto panels and Tiepolo ceiling paintings. It took me back. I was like “woah” this is inspiring. They’re from hundreds of years ago. From a time when people dedicated their entire lives – generations of lives – to making things beautiful. That’s a paramount goal in my work, I want to make beautiful paintings. It can still be beautiful and challenging.

NB: And it can still be dark!

KB: It can be dark! Again, spoonful of sugar. It helps you swallow some of the darker histories if they’re told in a beautiful way. At any rate I’m loving the book. The way he’s able to talk about how Caravaggio collapsed the space between the viewer and the painting. Even to look is to be involved with Doubting St. Thomas. To look is to doubt. The painting performs its ethos and message in its meaning. Some other artists – Hurvin Anderson, I’ve been looking at a lot. He won the Turner Prize a few years ago. Another person deeply invested in looking at background space and landscape to the point that he’s going over and over these spaces, redoing them, pulling them apart, reimagining them. And Patrick Caulfield, making these pretty paintings about composition and design in a very interesting sort of way. Other than that, I’m still reading Brothers of Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. I’ve been reading it for 7 years now. I’d gotten 500 pages in before grad school and put it down for a couple years, now I’m picking it back up. That’ll be a lifelong journey.

NB: Is there a body of work you’re focused on right now?

KB: I’m still fixated on the” Blue Series”. It hasn’t come to fruition the way I want it to. I want a complete show of these works. I have the title and I already know the organization, but I’m still working on building it up. Other than that, I’ve been working on a series of dark paintings, just playing around with how low of a value range I can work in. I think the two bodies sort of inform each other. In one you have the idea of the outdoors; the precarity and sublime of that outdoors tied to a radical blue sky, which is traditionally meant to connote safety, up against a series of works that are trying to convey intimacy and comfort in dark unseen spaces – which are traditionally meant to be scary or unsafe. It’s an inversion of traditional tropes of light in art history and culture. It’s not an wholly original thought: David Hammonds had that amazing piece where he blacked out an entire gallery and gave attendees flashlights that were impossible to use. To be seen is to be unsafe, and the safest point is in a corner in the dark where no one can see you.

NB: I think exploring the different levels of darkness in a series isn’t something you see all the time. Being able to find ways to interplay shades of darkness with some type of beautiful scene really plays against the notion we have in our minds that darkness is danger. I love how you’re exploring the binary of that darkness and light and how it plays on the viewer’s sense of safety and security and those traditional notions.

KB: I think also of the idea of wanting more, wanting to complete the picture with light. There’s a stoking of curiosity.

NB: And with that dark painting that you have, it invites the viewer to examine it closely to see how the shades are playing with each other to create that dimension. Do you want to talk about recent or upcoming shows?

KB: I was in a couple of interesting group shows towards the end of this year. “Voices” which was curated by Anwarii Musa had a really great collection of artists: Jeffrey Meris, Derrick Adams, Nate Lewis, my good friend Dominic Chambers. I was also in a smaller show in Brooklyn titled “American Socialist Realism” at Rumpelstiltskin gallery. I was shown alongside Martin Wong, Tseng Kwon Chi, Hannah La Follette Ryan and Clark Filio. I think the curators were asking interesting questions about figuration; placing realist figuration within the idea of propaganda. I think we can easily get locked into the idea of figuration/representation as an immediate celebration. Which isn’t always the case. You can represent terrible things. There’s various aspects of human life to represent. There are very important questions about who has traditionally been represented and a necessary redress of underrepresented bodies. But representation is complicated. Multiple poles can be brought into the idea of figuration.

NB: So you clearly have an inspirational story and I believe you’re destined for greatness. But what advice do you give to young artists? As a professor, what advice do you give to your students and to young artists figuring out if they should pursue a life as an artist?

KB: As an art professor, it’s funny how often this question comes up. I’ve had students come up and ask what they can do to become a successful artist. Sure take your work seriously, challenge yourself, but it really boils down to just not quitting. Don’t quit.