July 19, 2023

Artist to Watch

KATARINA CASERMAN

NB: What are some of your earliest memories of making art, and how does it relate to your work today?

KC: I often come back to this specific memory when we were children. We had these notebooks with blank pages that were called “memory books” and we gave them around to our friends and family so they would draw something in it and write something like ‘for the memory of Katarina’. I remember my mom one day she made this drawing of two deers, and back then it was one of the most beautiful drawings I’d seen. I remember I told myself ‘one day I’m gonna be as good as she is at drawing’. So my motivation was just to get as close as I could to my mother’s drawing.

With time I realized it’s just about practice and sometime around high school, I got pretty good at realistic drawings by observing things around me and copying them on paper. So these were my earliest memories of making art, trying to match my mental image with what I was drawing on paper. This always brought me comfort and happiness and something that has always made me feel something and luckily for me I was also good at it.

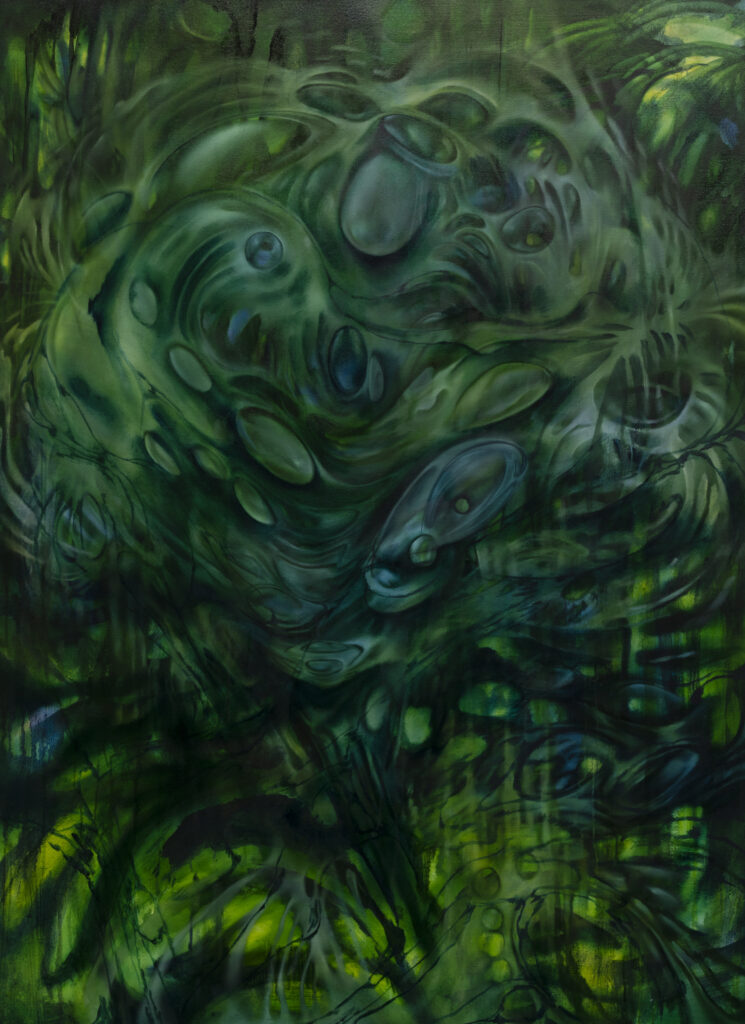

Now it’s of course very different. For me it’s not enough to just look, and mimic what I’m seeing. It’s more about ‘what else is there’? It’s not enough to just observe the world around me and then reflect upon it. I aim to turn inwards, reflect upon that and relate it to the external in order to create alternative structures of the visible reality.

NB: Can you describe the process when you’re starting a new painting, where do you begin? How do you move through it?

KC: I’ve attempted to do sketches many times in the past but it’s just not working for me. My body reacts completely differently in front of a canvas than it does sitting down and making a tiny paper sketch. I lose the momentum and it feels forced to match the painting to the sketch.

I usually begin by making a very thin layer of oil paint and then I take it off with a cotton cloth, creating an image by bringing back the whiteness of the canvas. The very first stages feel more like building or constructing than solely painting. I let the layers interact with each other, see the direction of different drips and just let the paint and gravity do its thing and let it sit for a bit. There’s a lot of sitting time involved because I need to be patient to recognize which trajectory the painting wants to go. I also need to take into consideration that the painting will change over a span of a couple days because of all the drying and dripping and other micro chemical processes. So this is how it usually goes, there’s a lot of waiting and observing and reacting upon it over and over again.

NB: So it requires a lot of patience, right?

KC: Oh yes absolutely, a lot of patience. Especially because there are many things that I do in the painting that are rather complex and I often forget how difficult they are. It’s quite simple though, complex forms require a high level of complexity and it’s impossible that you would achieve complex forms with simple solutions.

NB: Your work exists between opposing themes: it is organized yet chaotic, strange yet familiar, and dynamic yet still. Can you tell us more about these themes and opposites/binaries in your work?

KC: I used to say that my work has this notion of the opposite. I’ve been investigating this for over a year, ever since I came across Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein in which the use of words is so specific in how to describe certain conditions. For example when she says that the creature is reanimated, it goes from being ‘dead’ to being ‘undead’. So the creature was neither alive nor dead, it was in the zone of being ‘undead’. It was a walking contradiction. That just provoked me into thinking about how we can use language in order to expand the possibilities of the opposite.

For instance, if I ask ‘what’s the opposite of black?’ the answer would probably be white, which would mean it’s white and nothing else but white. If you say ‘non black’, then it would mean it’s everything but black, giving you more possibilities of what the opposite can be. When I talk about my work I use the proposition of ‘non’, meaning I don’t say there’s order and chaos but rather ‘non-chaos, artificial/non-artificial, movement/non-movement and so on. This sets the paintings in almost a ‘third zone’. I’m playing with the idea of opposites that exist in the same reality, so it has this notion of impossibility, like with these spaces where you constantly have some sort of a glimpse of light and at the same time a glimpse of darkness.

So it’s not about depicting something in particular, or descriptive, but they are setting a mood. When you stand in front of the painting you are getting primed/ready for the zone that you are about to enter, and this zone is the painting itself, but there is a specific mood that surrounds the painting.

NB: How does color relate to these themes in your process?

KC: It’s very, very, intuitive when it comes to color. At the beginning I don’t overthink it, I use any color that resonates with me in that moment because I know that the specific color will not determine the outcome. I usually just like to play with layering and getting different shades that don’t necessarily exist if they were only on one layer. These are colors you get once you layer one color over the other, in order to get a third one. It’s the optical mixing of the colors instead of just a physical one. I enjoy playing around with this because it gives me a unique experience when I’m moving around the painting. It seems as if the painting is changing all the time due to its multiple layered structure.

NB: Where are you currently drawing inspiration from? What artists, movies, music are you looking at?

KC: I’m not being the best artist right now because I don’t think I’m seeing enough art shows and I’m not intentionally looking at any visual art. On the other hand I am looking at all sorts of things every day because Instagram exists. I’m also the last person in the world to watch ‘Twin Peaks’ by David Lynch so this is something I’m currently obsessed with. It feels as if the whole series puts your brain into a dreamlike state so everything suddenly has a thin layer of ‘Twin Peaks’ over it.

I used to listen to a lot of music while I painted, and I still do, but now I mainly listen to podcasts or audio books. I recently realized that music has too strong of an impact on me. It will either make me paint faster, or slower, or evoke memories, which is very distracting. I switched to podcasts and audiobooks because as you follow the story, you’re in an ‘in between zone’ of being present in the painting, yet not fully there. I think of it being similar to how a pianist is when having a performance. When they are playing they are in this ‘flow’ estate where their body is acting instead of their brain.

NB: Can you tell us about any upcoming projects or exhibitions that you’re excited about?

KC: Yes! I’m represented by Tabula Rasa Gallery, and we have so many exciting projects coming up this year. I do have a group show in Beijing, in November and before that I’m also having a group show at a London-based gallery, which will be announced very soon and that I’m very excited for. Then there’s also art fairs and a couple of other things as well so it’s gonna be a very, very, busy year. To which I always add: being busy is a good problem to have.

June 19, 2023

Artist to Watch

KATE BARBEE

NB: What are some of your earliest memories of making art and how does it relate to what you’re making now?

KB: Well, my grandma always made these stained glass fixtures for the windows in her home, and I believe it left an impression on how I lay down shapes and colors in my paintings today. Even my use of wax and linseed oil I feel are reflective to the transparency of the stained glass. I feel like the lines I add into my work today are like the grout we would use to fill in the gaps of the glass shards.

I began painting at a young age and I was very interested in abstract shapes. I felt proud and excited about discovering something that was outside of the world we lived in, and I enjoyed the cathartic trance I would go into whenever creating an imaginary world of broken up colors and shapes. Shortly after I became a little more interested in fashion illustration and would draw dresses and outfits on figures as a way to almost live vicariously through my designs. I couldn’t wear these clothes because I didn’t have access to them and as a child I felt as if by creating it on paper I could own something beautiful. I think everybody makes art to escape from their own world, and for me the fashion design and abstraction really helped me delve deeper into my imagination as a child.

NB: So we can definitely see the stained glass windows, the stitching together, and the fashion design. Can you tell us about your process using mixed media? How did you incorporate the use of beads and stitching on your canvas?

KB: It all started when I was in high school, in this little punk scene in Dallas. I always sewed my jean jackets with band patches and pressed little silver studs into all my clothing because I felt this was my way to stay relevant. The stitches on my paintings now reflect the rawness of the stitching on my clothing in the past. Back then I was in Austin after graduating from college, and I was raising money selling jean jackets to move to Los Angeles. I bought a whole bunch of jackets from thrift stores and used the wood cut prints I made in school and trashed paintings to sew onto the back of them.

Once in LA I started adding patches on the paintings. I liked the idea of a living painting with loose fabric hanging from the painting and blowing around whenever someone would walk by, or when a breeze from an open window would bring it to life. Then I realized it was not sustainable and the pieces were going to fall off or fold/crinkle at a certain point, so I started fully sewing them down and I was very much touched with how familiar this process was with my history of sewing onto clothing.

At times when I’m working on the bigger paintings, I feel like I’ve created a social quilting circle because my friends have had to help me sew the pieces on. When someone is helping me sew onto the works it becomes a passing of energy where we’re passing the sewing needle back and forth, telling stories. Since I can’t go around the canvas and do this by myself it becomes a special process and I think about my family members in the past sharing this same experience when creating quilts with and for their loved ones.

NB: So what is the process like to build your fractured and intertwined compositions and these nonlinear narratives? Where do you start?

KB: I start with a few lines and I’m very impulsive. I see a blank canvas and I immediately attack it. Sometimes that leads me into a dark complicated place with the painting, because there’s no thought put into it. Yet in my practice I work with oil paint, and I think oil is not that forgiving. So I’ve learned to also approach a painting and sort of forgive myself when I make these mistakes. I will usually paint something impulsively and then I will impulsively cover it back up with a different shade of paint and at times it drives me crazy. As time goes on, I turn the painting around, I rotate it and see shapes coming out of it. At some point I would stretch my canvases on the floor and with whatever dirt was picked up, I would find a figure connecting the dots and tracing it out. I’m interested in seeing if I will ever have a calm moment in my painting process, but so far I have been enjoying this way of creating.

NB: I love it. So can you expand on your use of interior and exterior or inside and outside spaces? How does this relate to other themes you explore through your work?

KB: So I tend to ponder on this daily and I’ve figured that I sort of work with three types of locations: One is the place within myself that is fleeting and is an emotional place, the place that I create from my imagination to escape to. Then there is a physical space that is also fleeting because it is temporary and won’t be there forever. For example, I made a painting of my friend in her garden, which is planned to be sold to developers who will most likely destroy it and build something new. The garden is set on top of a hill, lush green and with a wooden bungalow with large windows in the middle. The space is like a Monet painting and although there’s sadness to painting a space and a moment that will eventually be gone, l also I feel there’s a justice with capturing this moment in time.

The third space I work with is also a physical location, and generally it’s a location that I have photographed when I’m walking or in a car. I usually take photos of storefronts and signs that I find interesting, then I screen print them onto fabric and sew them as patches onto the paintings. So far I have only done this with photos I’ve taken in Paris and Los Angeles, but the world is always changing and I am always growing. I believe that it is important for me to capture these stamps in time. Of moments, feelings, energies, and locations.

NB: Incredible. Do you have any upcoming projects or exhibitions you would like to share?

KB: Yes, I’m going to be in a group show at Albertz Benda, showing work next to the late Ken Kiff’s work and many other great artists. I’m also working on my presentation for Sotheby’s Institute and a show at Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles in 2025. I am very much looking forward to continuing my career now in New York, and excited to see how I will grow out here. Thank you so much for coming by my studio!

May 12, 2023

Artist to Watch

DYLAN ROSE RHEINGOLD

Nicole: So when did you first begin to paint and what drew you to be an artist?

Dylan: I don’t remember if there was a specific instance when I realized I wanted to be an artist. I’ve always been painting and drawing, and both of my grandmothers were artists or creatives in some ways so from a very early age I was always encouraged to use my hands. When I was younger I had some anxiety struggles and I think a big outlet for myself, that was encouraged by my family, was drawing. Drawing was always just very natural, it simply stuck with me and I can’t imagine my day-to-day without it. A lot of artists that I talk to, they say I didn’t have a choice, and this is who I am, although it sounds almost corny saying it out loud, but it’s very much true.

Nicole: So could you tell us about the storytelling narrative aspect in your work?

Dylan: In terms of the storytelling aspect I’m working with a narrative that’s non linear. When people are looking at my work, and also when I’m making the work, I like to think of all of the paintings in dialogue with each other. It’s hard for me to pick apart or speak to only one painting in series. The reason I like working in series and working on multiple pieces in unison is because I like to see how they interact and talk to each other. What’s also interesting to me in terms of the narrative is this aspect of self discovery, thinking about my identity and taking a look at girlhood. I’m interested in the transitional space between girlhood to womanhood, or even in a broader sense, childhood to adulthood.

Nicole: How is the process of painting and the use of mixed media related to this narrative?

Dylan: The first time I did a mixed media painting was when I was studying painting and screenprinting a couple years ago in Florence. Before that I studied illustration, so I was learning and going through an education that was focused on mastering the traditional skills before you could move on and come up with your own style. I had a really hard time with this more traditional education and got into a lot of altercations with my professors in my undergrad because I really didn’t like that way of learning. I’m grateful for having those skills mastered now, but it was really frustrating at the time.

Before that, I was never using mixed media because it wasn’t the traditional thing to do, and it wasn’t until Grad school, after that semester in Italy, when I started thinking about all of the layers I was trying to address through painting and how that fell hand in hand within my own narrative. Speaking as someone who comes from a mixed background in terms of race and religion, I think it also naturally evolved into pulling all these different materials together and layering, and layering, and building these pieces without realizing at the time the connection it had with who I am and my background. I also love mixing materials that are a bit more traditional or high end with things that you wouldn’t expect, and that speaks to the parallels of adolescents and the coming of age. I have on my desk these packs of sparkles or glitter that I’m mixing with these expensive oil sticks and navigating how they can work together and what emotions that can evoke: It’s the girlhood and the womanhood in one.

Nicole: What do you have pinned to your walls and what books do you have open right now?

Dylan: I have a lot of drawings currently pinned or taped to my walls, and all of these start off in the automatic drawing or automatic writing, surrealist automatism manner. So I’m not trying to think about it and I’m just trying to let the subconscious sink in. What I believe is successful is that they give off a dreamscape and surreal feel to them while also speaking of the narratives I’m interested in.

The books that I have open at the moment are Katherine Bradford, Rita Ackermann, Cy Twombly, David Humphrey, and a Tracey Emin book.

Nicole: The expressive line across all of them, you can see how that transgresses into your work.

Dylan: Thank you, that’s a big compliment! Also there’s Philip Guston, I feel like a lot of people have been looking at him recently, but he’s like my everything.

Nicole: So tell us what are some of your upcoming projects or exhibitions that you’re excited about.

Dylan: I’m very excited about my solo show at T293 Gallery in Rome opening May 11th through June 1st. The show will be taking form with eight large scale mixed media paintings and six wood panel studies that are also mixed media. These studies aren’t really traditional studies because they don’t look like an underpainting or an outline for any of the large scale works. There’s a layover between the objects and the symbolisms throughout those drawings and I think if you take your time and really look at the group together, you’ll find that there’s a lot of crossover with the larger works. After this show in Rome, I’m preparing for a solo show in the winter at M + B Gallery in Los Angeles.

March 15, 2023

Artist to Watch

LINDA CUMMINGS

NB: Linda, when did you first pick up a camera and what drew you to become an artist?

LC: Growing up, my father’s Zeiss Ikon rangefinder was always nearby. He carefully composed the photos of my childhood, and that of my 6 younger brothers and sisters, in ways that gave the appearance of happiness and harmony that were far different from my experience. When I set off for college he loaned me his camera and I took it with the determination to discover the world through my eyes. It’s ironic that the same camera my father used to cover up the messiness, the cruelty and contradictions in our family is the same one that allowed me to disarm and reveal. With a bus ticket from my grandparents and a scholarship I won to the Cleveland Institute of Art I began my new life in search of a community of people like me, with questions like mine. I went to study painting but was met with a very antiquated view from many (mostly male) professors that would often dismiss female students. I noticed an inverse relationship between the number of female students entering school and those graduating, so I went to the Director and suggested they add more female faculty. Instead, they rescinded my scholarship the following semester, so with the encouragement of my friend, April Gornick, who left CIA the year before to go to Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, I finished art school in Halifax, Nova Scotia. There I found a thriving avant-garde community of conceptual artists – Laurie Anderson, Martha Wilson, Katherine Knight, June Leaf and Robert Frank. I flourished there in its progressive, vibrant intellectual community, beside the open sea. It opened my eyes to performance art, art on the move.

NB: So at this time you’re studying painting, how did you come to integrate the performance aspect into your practice?

LC: In Halifax I began making cameras of my own: I made “pin-hole pigeon cameras” inspired from World War II spy cameras, when pigeons would fly over enemy lines with tiny cameras attached to them. I made a flock of seven pinhole pigeon cameras, each one with a string attached to open its shutter. I’d sit on the bench at a public park, waiting for live pigeons to interact with my decoy pigeons and then make a “pigeon pinhole” picture of the interplay. Performing my artwork in public gave me a place for my work to be seen and so art-making in the open became my conduit. My first artwork purchased by a museum was a silver gelatin pigeon photograph acquired by the Lehigh University Art Gallery in 1979.

Project: Slippages (1992-2022)

NB: Your work is characterized by working in series. What is the process to help you determine each of these new series? How do you know the beginning and the end?

LC: When I start a project, I have mulled it over for quite a while. Once I find the materials that speak to, or reveal the idea, the process accelerates and becomes more organic and intuitive, but I always return to a conceptual basis. An artist gathers lots of impressions, whether in photographs, drawings, writings or sound scores, but knowing which one to save and follow, and which one to let go is the hardest part. Looking back now I see a recurring fascination in my artwork about the interplay of visible and invisible forces shape our lives. I think this goes back to my initial pigeon premise, the idea of the co-creation of the image by both subject and object, like the Heisenberg Principle that the act of observation changes the thing being observed. The end of a series is kind of an illusion. There really is no end, just a transformation in material or technique or subject matter. I mostly wait for something in the work to announce its own completion.

NB: Your current exhibition Slippages at 89 Greene was initially developed over a span of 10 years (1992 – 2002). Can you tell us a bit more about revisiting this body of work 20 years later and how has the work evolved over time?

LC: Slippages is a project that comes out of a desire to literally transcend the gravity of the past and reclaim what may have been left out, or invisible. Over time, though, I realized that what began as an attempt to picture hidden power dynamics of gender, was evolving into picturing the changing dynamics of power itself. A radical new invisible technology was simultaneously reshaping our landscape and lives. At the end of the millenia, once secure infrastructure and systems of knowledge based in the physical world began morphing and disappearing into a digital reality. I witnessed previously defined hallmarks of society, architecture and tradition begin to crumble and couldn’t help seeing the shifts in the social, cultural, economic and personal domain as inter-related to our increasing digital dependence.

For Slippages I found objects and sites that held cultural significance, and had power and history embedded in them. The garments I chose, seven slips, held powerful memories and associations. The slip was not only a uniform of gender, but also a potent word – both noun and verb – that resonated with the actual power slippages I saw happening in the world. Although the slip was a constant feature in the photographs, my initial subject of identity and resistance had transformed into a meditation on change itself – another invisible force, like the wind – that can be seen by virtue of its impact on the visible world and physical beings.

NB: So there’s this aspect of atemporality in your work and a sense of movement, do you want to just expand on that a little bit?

LC: I like to make artworks that tap into a sense of on-going being, an organic flow of time and process. Susan Sontag says “…There is no final photograph…” because the desire to look and to see and to learn is endless. Art and tradition transcend time, I think, because they spring from a human need to connect, to make meaning and to feel safe. Unconscious processes and unresolved conflicts, like wars, transcend time. They keep on going. Isn’t this why, 50 years after Roe v. Wade, we are coming back to the same question of who’s in control of the female body, even though we all thought it was settled law? Whose interpretation counts? We have differing interpretations and perspectives on events because we all see them through the filters of our own time and place. I search for a moment of recognition where reality and my imagination meet. It is at this moment, this intersection of inside and outside, the convergence of now and then, that I click the shutter and the photograph begins.

There was a project I did for four years, from 2004 to 2008, where I stood as a silent sentinel during the Iraq war in the same spot in front of the U.S. Army recruiting station at Times Square. There I made pictures of young men and women going through the doors to enlist. In the frame was also the war of words and images – glaring screens and billboards of military and commerce competing for attention from passers by. I took 24 frames within 24 minutes to underline the phenomenon of the persistence of vision and to reference the way cinema and news media construct their narratives. Afterwards I pieced frames together in photographic scrolls so the viewer could slow down and digest these different impulses and images screaming at each other.

NB: Amazing. Do you have any other upcoming projects or exhibitions that you would like to share with us?

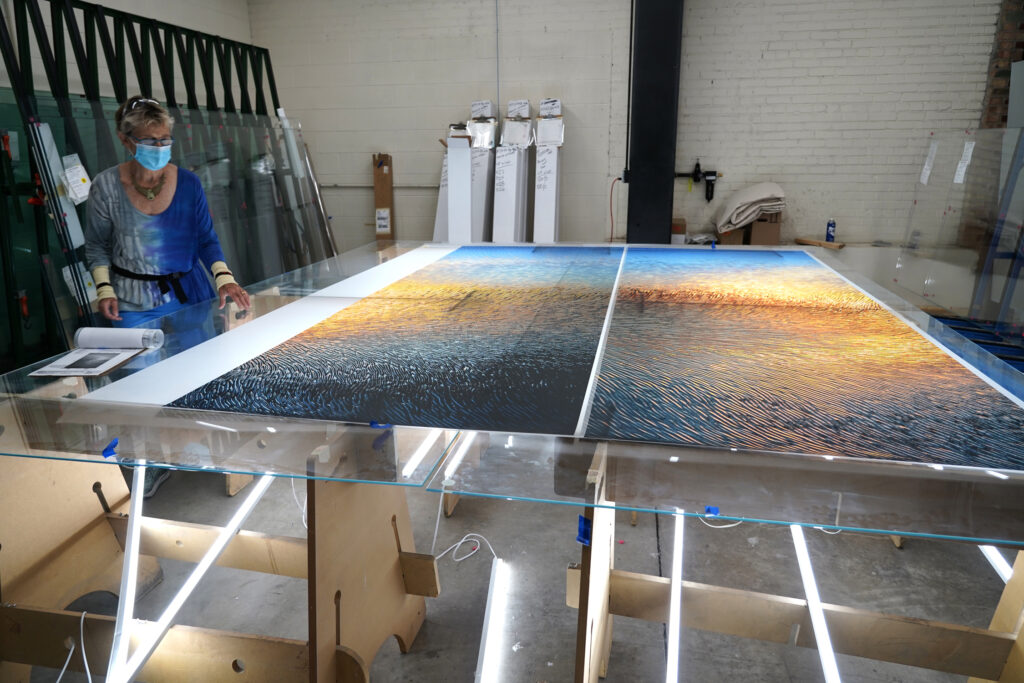

LC: Yes, on view through March 25th is Slippages at 89 Greene, the project space for Signs and Symbols Gallery in the Lower East Side. And I am excited to be working on a large project titled Genesis 1.2 – a large 10-foot x 7-foot photographic glass artwork to be installed in June 2023 as a permanent installation in Temple Beth Tikvah in Madison, Connecticut. This project engages two passions of mine: understanding properties of light and advocating for the health of water bodies, rivers and estuaries that feed into Long Island Sound. It’s an artwork that was created in a collaborative spirit with members of the community. The guiding premise for the Ark given to me by the Rabbi was Genesis 1:1-5 and the birth of light from darkness, with the spirit of God hovering on the face of the waters. On the first morning of Hanukkah I captured a spectacular sunrise through a glass device I constructed to distort and expand the light rays, separating them into a shimmering spiral of color and transparency. The effect is iridescent, like an impressionist painting. I am constructing a physical space in a sanctuary, creating a stage within which to present an artwork intended to uplift the viewer, metaphorically, into a state of reverie, awe, and inspiration.

February 2, 2023

Artist to Watch

KEVIN CLAIBORNE

NB: Can you tell us what are some of your earliest memories of art and how do they relate to where you’re at with your practice today?

KC: I believe my earliest memories of art were that my family had an Ernie Barnes print in our living room at home and I think it was the Sugar Shack painting. Also, I was always a doodler when I was a kid, and I remember I would get in trouble a lot for drawing in class. I think I’ve always been creative and drawn to art although I didn’t really go to art galleries or anything like that when I was younger, but I’ve always been interested in art making in some capacity. Actually my father, he was a photographer on the side, but as a kid I didn’t view that as an art form, just for documentation. It wasn’t until I started learning and I taught myself how to do film photography that I realized it had such power to be used for art. Once I started practicing, I got more into it and eventually developed my own conceptual practice.

NB: Your work and writings are characterized by themes of mental health, identity and trauma. Can you tell us more about how you approach these topics?

KC: Through my writing I always try to maintain a certain level of honesty, transparency and introspection. After going through a lot of mental health issues myself, a few years ago I realized that writing was one of the best ways to deal with and understand those issues and concerns. Also making work about something that I’ve personally experienced helps me understand more about myself. After speaking to my mother recently about mental health struggles that she also dealt with, I started to learn more about how these things can be cyclical and repetitive within my own family and within my friends’ families. I try to use that in my work and writing as a tool to understand why these patterns continue to reoccur as I search for solutions to break those patterns. I also have a background in math and one thing you learn in math is that almost everything can be broken down into some sort of pattern. I’ve always been a logical thinker looking for patterns, but art is a creative way to isolate patterns and change your understanding around certain issues. Art making also helps develop your understanding of yourself in relation to those issues, whether on a social micro level or a macro, wider level.

NB: Given the wide range of disciplines within your practice, video, collage, sculpture, writing, photography, silkscreen painting, how do you determine which medium to work with next? Do you think different mediums apply to different concepts?

KC: Absolutely. I love working in multiple mediums because I feel like it allows me a level of freedom that I believe all artists should give to themselves. I don’t think any artist should be boxed into one medium or mode of making. I think you should definitely take the time to master at least one, yet I think it’s more beneficial and advantageous to your practice if you try to do things that you’re not an expert in because you end up learning new techniques or approaches to your main mode of making. I also don’t like limiting my approach to the one that I’m strong in, because you don’t always know the one you’re the strongest in (you might think you know, but you don’t always know).

That’s why I try to work with the idea first, the medium second. If I work that way, then it gives the idea more space to evolve beyond me constricting the idea into a box of “this idea has to be a photo, or a painting, or this idea has to be a sculpture” If I just say this is the idea and then allow that idea to tell me how to present it or not present it then I think the idea gets to live longer in a better way.

NB: So what are some artists or people that you admire or that you’re looking at right now?

KC: I’ve also been listening to a lot of Gil Scott Heron, his spoken word and older albums and looking at the artwork of Tomashi Jackson and Torkwase Dyson. Those are probably the only two as of this week, because it’s ever changing and there’s way too many talented people to keep track of. I try not to get too caught up in what other artists are doing because it may be distracting, although I think it’s a good thing that nowadays we can see what people are doing through social media – what they’re doing within their own practices and if they’re taking risks.

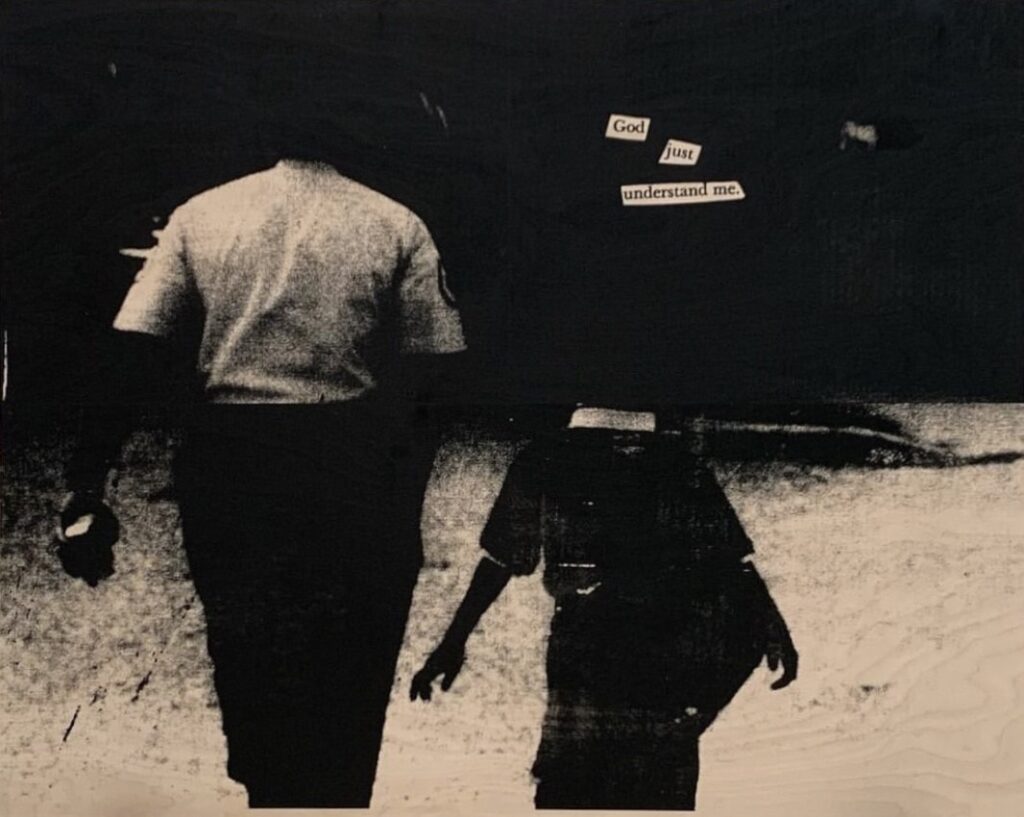

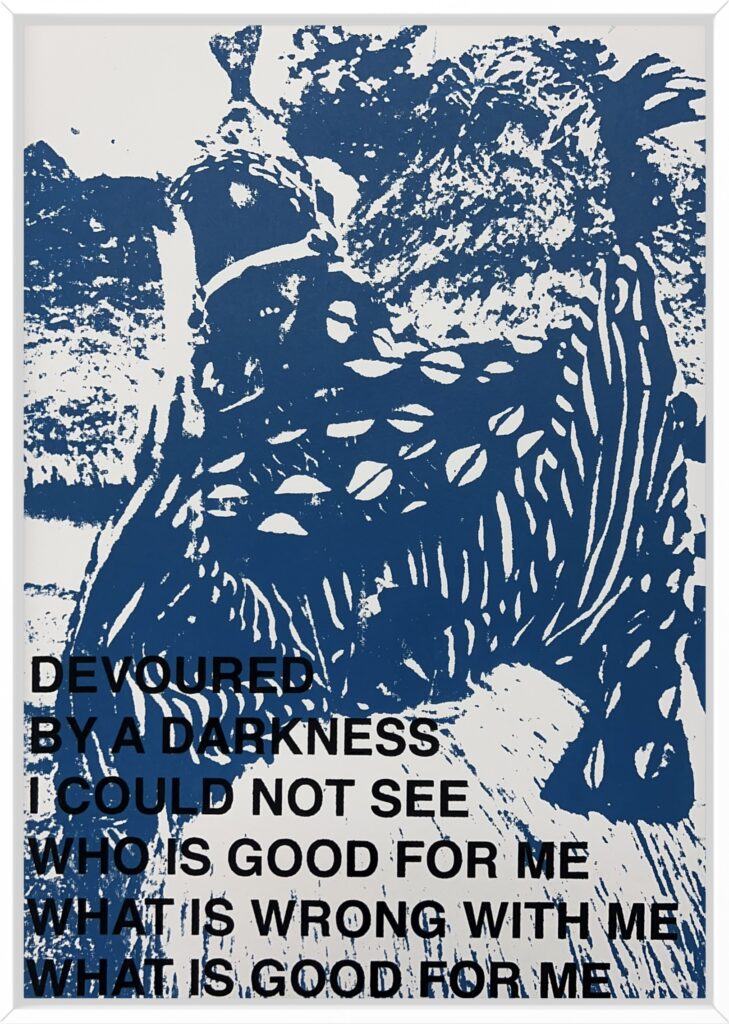

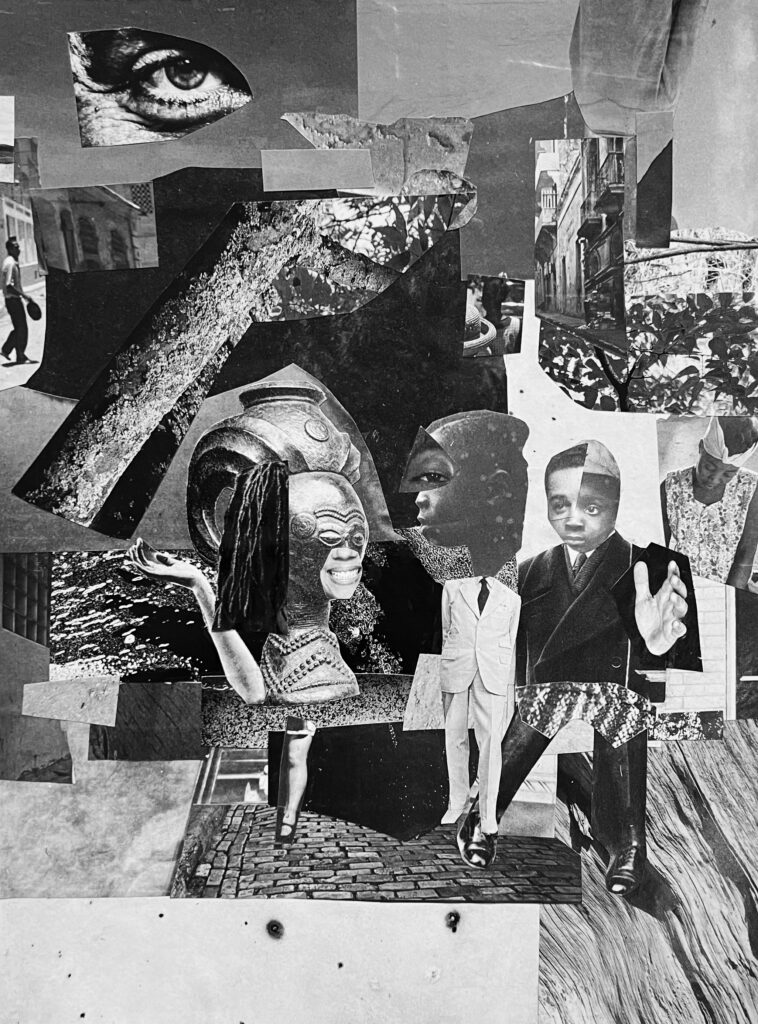

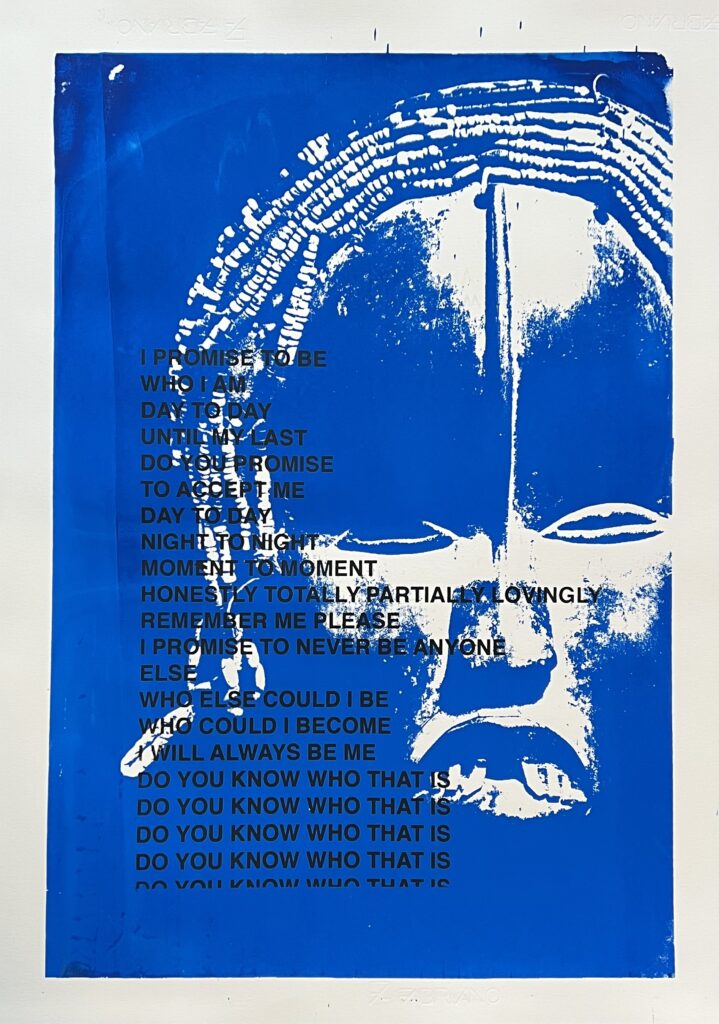

NB: So can you tell us about your most recent exhibition, Understand Me at Osmos Gallery and the group show Dark Matter at Kates-Ferri Projects?

KC: The solo show at OSMOS consists of photo collage and paintings. The series of paintings are titled The Unconformity Series, and they’re inspired by the Great Unconformity which is a missing chunk of sediment in the Earth’s crust about 100 million years to 1 billion years long. The image and text works in the show consist of found imagery from my family archive and from books that I own referencing West African sculpture and art. It’s a show about fragmentation of identity, it’s about lost history, and it’s about reclaiming or recreating one’s personal and historical and familial narrative. The Dark Matter show at Kates-Ferri Projects is about how dark matter exists in space, but it’s not something that can be observed and the group show takes a bunch of different approaches to documenting or creating that which cannot be observed or captured. The works that I have in the show are one of the Unconformity paintings and one collage, a piece of abstraction with a piece of fragmentation. I love how the show came together, there’s a lot of variety within the works and mediums, and how people are using those mediums in unconventional ways.

NB: So lastly, what are some projects that you’re excited about in the future?

KC: I’m working on a solo show that will be in Sweden this year at Public Service gallery in Stockholm and working on a group show in New York for June. Personally, I am trying to use more of my writing within my work. I’m really interested in trying to figure out different ways that my writing, my language, and words can exist within my work, and trying to step outside of my comfort zone when it comes to the way in which I use my text and poetry and the word itself.

January 10, 2023

Artist to Watch

GABRIEL MILLS

NB: Can you tell us about your experience with art before Yale and how you have arrived at where you are now with your practice?

GM: My training was classically inclined. I maintained non-academic experiments outside of my studies. At Yale, I synthesized my interests. Currently, I follow my hunches, and unforeseen space opens up. Simultaneously, I revisit familiar territory with an adjusted level of rigor and perspective.

NB: Can you speak on how the physicality of paint is used to address the subject matter of your work?

GM: Love, time, and weight are central subjects to my practice. The range from heavy topographical to smooth atmospheric surfaces is a byproduct of a considerate process for those subjects.

NB: Could you share more about your painting process and in what ways the process differs between your abstract and representational work ?

GM: On the surface, the abstract paintings aggressively deal with the physical nature of oil paint; The representational work moves towards non-narrative while weaving in and out of legibility.

I’m bringing my full self to each work, to then go on an arduous journey. The destination isn’t ever a physical location; it’s an internal realization. The outcomes of said process aren’t predetermined to be on a binary of aesthetics. I understand the distinctions between modes of painting, but I don’t think in those terms while I’m creating.

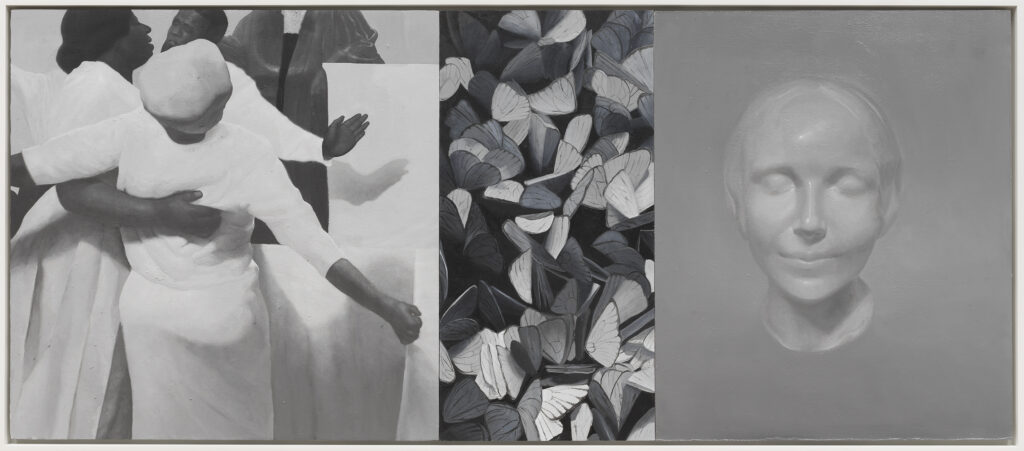

NB: What is the intent behind the compositions of your diptychs and triptychs? Is there a particular story or narrative to these works?

GM: There is no specific grand narrative. Instead, there are themes for contemplation; occasionally, a piece will be narrative. Each painting is a new opportunity, and none of them are promises. My motivations are to examine relationships by forcing familiar situations to exist alongside an unlikely companion..

NB: In your recent show “Butterfly March” at Alexander Berggruen there’s a series of abstract ‘color field’ paintings. Could you walk us through the process behind these works, and tell us a little bit more about this exhibition?

GM: The “Butterfly March” exhibition contained a wide range of approaches to painting revolving around existential themes; Living multiple metaphorical lives, dying through the flesh to be reborn in spirit.

NB: What are some projects in the future that you’re excited about?

GM: Painting is most exciting; seeing what comes of it all is exciting. That’ll always be my case. An exhibition catalog of “Butterfly March” will be coming out soon, via Alexander Berggruen. Regarding exhibitions, my next solo show is in March 2023, with Micki Meng gallery in San Francisco.

December 6, 2022

Artist to Watch

RACHAEL ANDERSON

NB: What are your earliest memories of art?

RA: My upbringing on an apple orchard and flower farm is a huge influence on my art. My earliest memories are of making things out of found materials outside while my parents worked in the orchard.

NB: Can you walk us through the process of your work, from the moment you chose an image for reference until completion of a painting? Would you consider your work to be premeditated or intuitive?

RA: I usually find objects and spaces that have a certain affect, mood or shape and put them in relation with other things and spaces. Some of my favorite things to paint are bones, leaves, flowers, wheels, feathers, pumpkins, compost, and thickets. I try to paint from observation initially and as the painting develops, I abstract certain parts of it. I don’t start with a full picture of the image I am making. I begin imagining a bouquet of objects that can communicate ideas related to cycles of growth or decay, non-human agency, human relationships to the biosphere, and biological fascination. Then I find things in the world and set them up in my studio or go out and paint them from observation where I find them. I sometimes paint from photographs in order to record specific lighting situations and it’s always a balance between referencing photos and looking at things directly.

NB: Photography seems to play a very important role in your practice, can you tell us more about how it has influenced your choices as a painter?

RA: I use photography as a research tool for finding things I want to reference for paintings. Polaroids distort things giving them an effect almost like an aura that I find ethereal and haunting. I try to replicate this aura with painting. The way polaroids develop in the atmosphere and space where they’re taken reminds me of painting, too. I love to photograph objects in natural lighting during certain times of the day and night such as very early in the morning or right before the sun goes down. This adds drama to whatever I’m looking at. I notice how light is always changing things–nothing is ever still.

NB: What are some of your references in art history that impact your practice today? What are some artists you are looking at right now?

RA: Women surrealists and spiritualist painters like Leonora Carrington, Agnes Pelton, Georgia O’keeffe, Max Ernst, Victor Man, Fra Angelico, Bjork, Francesca Woodman, Albrecht Dürer. More specifically, I love O’keefe’s masterful painting. Her closeup crisp florals reinforce for me the wonderfully bizarre forms of plants and bones, they have character and personality and somehow it feels as if they don’t care about us. I love Fra Angelico’s colors and his use of light and Max Ernst’s nature at dawn paintings. I am attracted to classical paintings for their spiritualism and emphasis on light. I like the challenge of framing things with light that speaks to both the 21st century and the past, working in this way feels as if traveling in time.

NB: Can you tell us what is the intent behind your use of light and color and how this is related to the titles in your work?

RA: I reference light and color in my titles to describe whatever phenomena I’m pointing to in the work. Some titles reference the golden hour, twilight, the coolness of a mirror, the spectral quality of green leaves, the blue radiance of the light cast by the moon, the fluorescence of a light bulb, the toxicity of cobalt. The distinct seasonal lighting within which the painting is made is often very influential to its title, and central to the work itself.

NB:What are some projects that you are working on or are excited about in the future?

RA: I’m excited to explore my hand in painting more and more and to continue to surprise myself, for now I am focused on just painting in my studio. I am also very happy to be included in a group show titled the Floral Impulse curated by Xaviera Simmons at David Castillo in December.

November 2, 2022

Artist To Watch

RACHEL LIBESKIND

NB: Can you share your experience with art as a younger woman and how you arrived at what your practice is today?

RL: I am very lucky to have been raised in a very artistic family. As a child I was always encouraged to follow my dreams and was told that art was the best thing you could do with your life. I spent a lot of time making art, although as a child and young adult I was much more involved in acting and singing, and I did a lot of that professionally as a kid. At university I got a degree in French Literature; since I finished early and had two more years left, I figured I would get another degree in visual studies. I had a great professor who suggested I should be an artist, so this is where I ended up. (I also graduated into a profound recession and watched the government and economics majors struggle to find work – being an artist made sense in that context).

I now realize that I’ve had great luck in terms of showing my work, selling my work, and being able to actually have a valuation of my work.

NB: So can you speak on how the process of collage, installation, video and performance inform each other and how does your approach vary between them? How is a live performance different from other works?

RL: The way I think about it is that all of my work has a collage logic. That is to say, I allow myself to freely take and mix any element I want in whatever form I’m using it –that’s the beauty of collage, that it’s the most liberating form. A lot of artists are very specific, and I have been told many times in my life that I should narrow my practice, but I just can’t. I am someone who’s very multifarious, and I really believe that every idea I have that I want to transmute to work deserves its own form and deserves to be critically examined in whatever form it needs.

The performances are a little bit their own world, they serve to me as this connective tissue between my research and my studio practice. For me, performances are an opportunity to imprint people in a different type of way because it’s the most ephemeral form of art. I think a lot about my performance practice as an experience that someone has of me that they’ll never have again. In this way performance is an incredibly unique and wonderful thing that I believe all artists, even people who have nothing to do with performance, should pursue.

NB: How do you describe the parallel between the personal experience and community engagement in your work? Are there certain projects that you feel are more personal than others?

RL: Yes. The performance work is always hyper personal because I’m there as the work, and I’m always telling a story. My studio practice and the work that gets shown in galleries and institutionally is personal because it’s me making it, but there’s a negotiation that happens with how much vulnerability is allowed to permeate into the presentation of work. Vulnerability and authenticity are, in my opinion, the key to what makes art “good”, although this also can make things too heavy-handed at times.

Another important aspect is history, the central framework of my practice. History is collective, but the way in which we encounter it is personal. I’m interested in the different ways in which we all think about history, the ways in which we were all taught history, and the ways through which we all connect to our own histories. It is within those fault lines, where the personal comes up for me and for my audience.

NB: Your work often consists of image archives that reference history. Can you talk about this process and how the work evolves from the initial research towards a finalized work?

RL: The initial research is often a very long and slow process. It begins when I encounter an image and I think “what is this crazy photograph? I’ve never seen this” or “who took this? Where does it come from? Who are the subjects and why were they chosen?” And then for years I will slowly build research around it, meaning there’s often multiple concurrent research projects happening in the studio. Luckily I have brilliant people to help me with it.

What ends up happening during this process is that my specific interests or questions begin to coalesce and I decide how narrow or wide the archive for a specific project is: then I make a choice about the form the work is going to take. Once I know whether it’s going to be a video, an installation, a performance and/or some sort of collage, I begin to build the archive that belongs with, and informs, the work. In the end every work of mine has its own archive and that archive comprises a selection from multiple archives that exist digitally or in real life. When the work is done, the archive is closed and I usually make a book, a password encrypted website, or something that encases the archive.

NB: Can you tell us about your most recent show, Transparent Things at Signs and Symbols and your new body of work Windows?

RL: My show at Signs and Symbols is a collection of 10 paintings (or as the director of the gallery calls them assemblages) that are made out of PVC, latex, silicone, paint, staples, linen, and paper. I basically wanted to work on a stretcher bar, to work on canvases, just because I really love Painting. I collect a lot of paintings myself but part of why I don’t usually paint, and part of why I’m sort of a mad woman in terms of how many forms I like to use, is because I’m always grappling with this masculinity of painting. Perhaps it’s because I studied with Benjamin Buchloh that I had this idea of post-war 20th century painting: I love Richter, Kiefer, Newman, Rothko, and Pollock, and these are all incredible painters, but I’ve always felt under a kind of suffocating claustrophobia of that work as a woman.

Additionally, painting is so incredible because for thousands of years, before altars and frescos, screens and photographs, we’ve been making life-like marks on walls such as cave paintings. There is something deeply innate in that process and that encounter. In the Renaissance for example, the painting that lived in the home of a usually wealthy person was like a window, this other world or portal that you could transport yourself to, in the way that a screen is today. These works at Signs and Symbols are a meditation on that, both on my grappling with “what is painting?” and what can I get away with calling a painting and enshrining myself in the legacy of great male painters.

NB: Would you be able to share with us any upcoming exhibitions or projects that you’re excited about in the future?

RL: Of course. I’ll be doing a very exciting Christmas Nativity scene for Half Gallery Annex that will be up for a few weeks over the holidays, at the corner of East 4th and Avenue B. I’m not actually Christian, but I really love nativity scenes because there’s no irony in them, and it’s such a wonderfully direct opposition.

I’m also working on a project in Sicily about migration and diaspora. Sicily has such unbelievable, untouched, incredible churches and iconography that’s around, and so many people who are taking over abandoned churches and making shows in them. This whole art scene I’m starting to discover there is amazing.Lastly, I am very excited for my first solo museum show in 18 months, at the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University. I’ll be going to Alabama in a few months to do more research in their archive and I’m really looking forward to it.

October 5, 2022

Artist to Watch

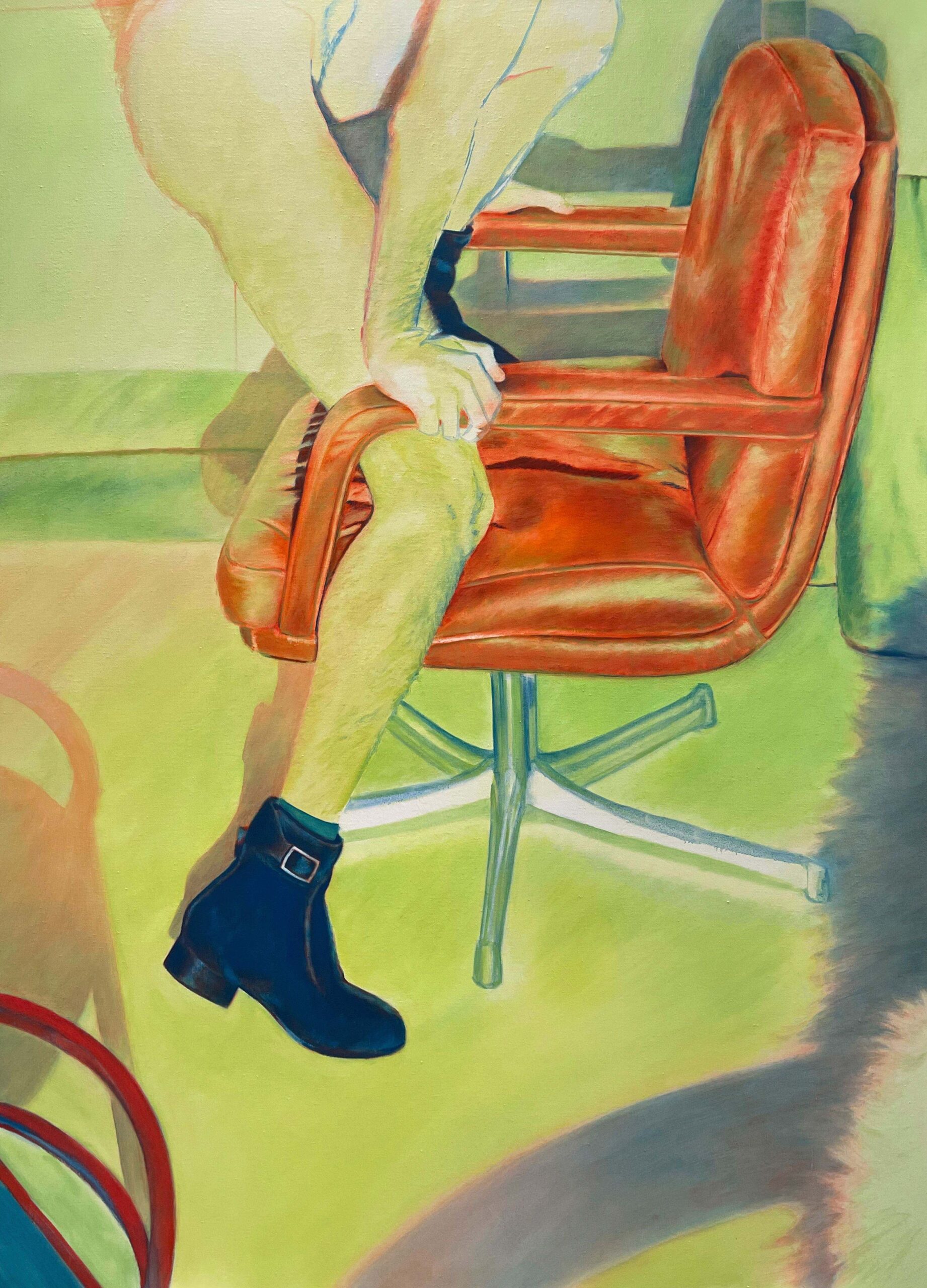

NANA WOLKE

NB: What are your earliest memories of interacting with or experiencing art?

NW: As a kid and only child surrounded by adults I spent a lot of time on my own, often drawing, as that was the sort of medium that came quite naturally to me. My primary school teacher picked up on my enthusiasm for art and enrolled me in several different competitions, so I had a few experiences showing my work early on.

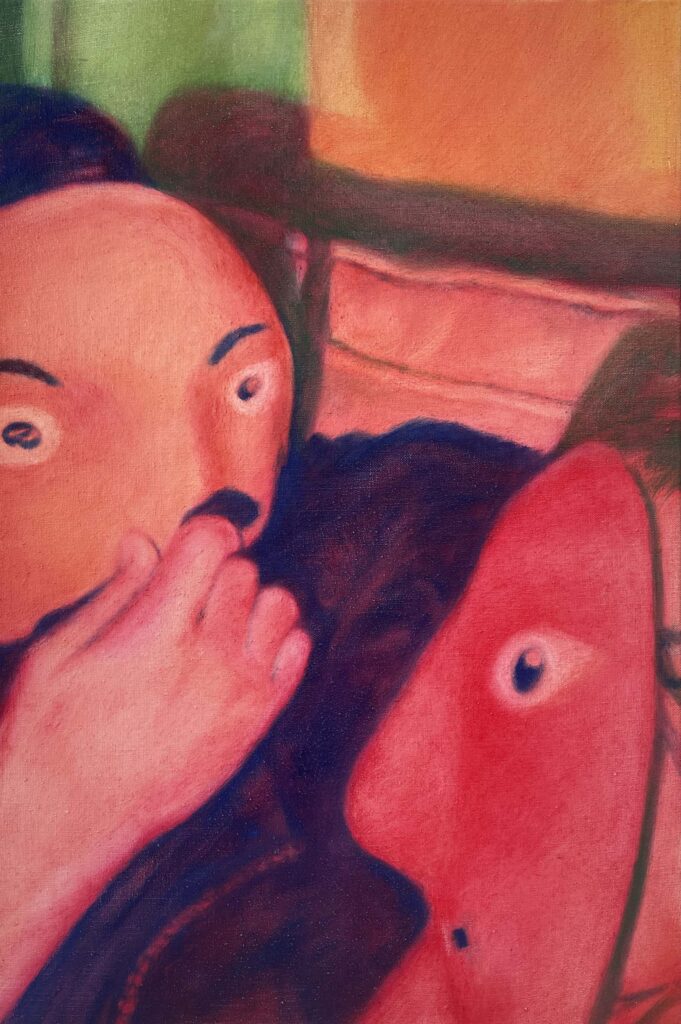

The other big influence came from being glued to the TV set during the post-socialist Slovenia of the early 2000s. Back then, the shift to the capitalist embrace of US culture was something that I was absorbing rapidly, always imagining this near fantastical world behind the screen. This thin line between reality and fiction is something I continue to examine in my work today.

NB: What is enticing about painting as a creative material for you?

NW: My undergraduate education in Slovenia was very traditional, an academy style of program, where we had nude models and figure drawing classes, very rigid and structured. My professors thought of painting as something that had already been done. Video and installation were much more common and although painting was still treated as dead, it was also regarded as a craft of the highest order that needed to be studied in excruciating detail. I was distracted from painting for a year or so, but I naturally gravitated back towards it. I don’t believe you really get to choose the tools with which you explore and work through things.

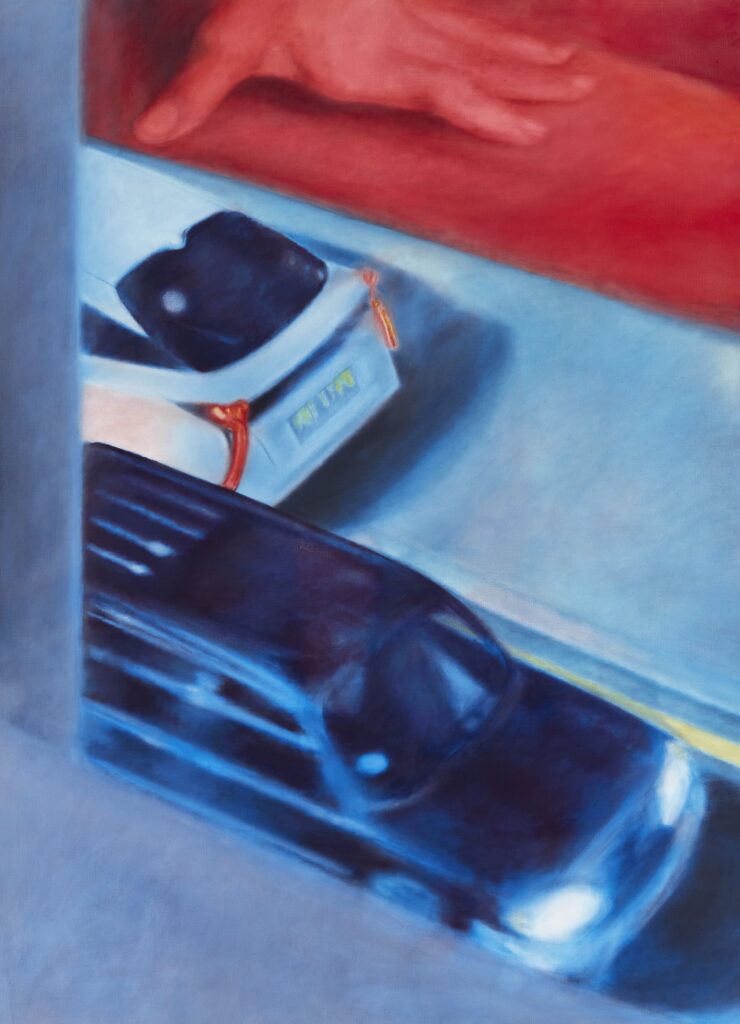

Today I’m most excited about the element of time in painting, which is perceived as much more permanent than, for example, a freeze frame from a film or a photograph. Bringing in the logic of a slippage of a moment (the wrong frame, rather than the climactic moment itself), as well as incorporating other elements like sound, shifts the viewer’s perception of time and space within the work and away from more traditional conventions of the medium.

NB: Your work borrows from the visual language of cinema, what kind of influence does moving image have in your practice? How do you arrive at the visual references used in your work?

NW: I’ve always been excited about moving image, especially cinema, but it took me quite a long time to understand the full potential of how it could play a role in my practice. Around the time when I was graduating Goldsmiths, I started working with specific locations and setting private performances. I would photograph both real and scripted situations, recording atmospheric sound and other material evidence of the setting to use as reference for my work, and as inspiration for sound pieces and prop-like sculptures. Really, my works are first and foremost artifacts of these private events.

The spaces that I gravitate towards are often transitional spaces, historically pushed to the fringes of cities or fully operational when most of us are asleep; from short stay hotel rooms and public garages to inhabited apartments, and above all, the people who frequent them.

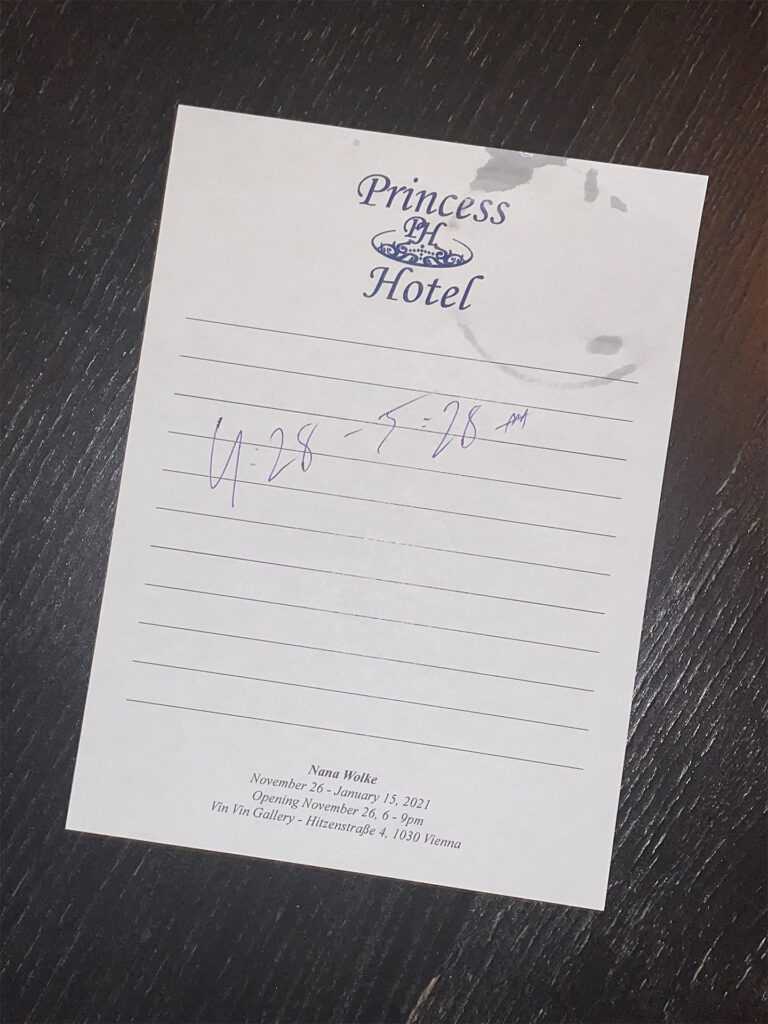

One of the spaces I recently worked with was a two star hotel in Kings Cross where I rented out a room several times over a period of a month to familiarize myself with how people used the space. Then I developed my own fictional narrative, a meeting of two potential lovers scheduled between 4:28 and 5:28 AM. I brought in actors – which at the time were really just my friends and we responded to this context together during what seemed to be a nutty experiment. The nature of the work is pretty fast too since we never have permits. I take the photos with my phone and use hunting lights instead of proper film lights which give a familiar cinematic effect but are easier to carry around.

NB: Your paintings have a characteristic monochromatic palette. What informs and affects the choice of color? In what ways do you think of color to convey different emotions and scenarios?

NW: The color range actually comes from me using hunting lights to stage with. These small handheld torches have an intense beam and come with four different color lenses – red, blue, green and yellow. I consider the kind of implications that colors have in terms of how the space is going to be portrayed, what kind of atmosphere it will create, and consequently how the viewer might approach it.

I was initially drawn to the color red, which both in art history and cinematic language, but also daily life, has a lot of different connotations that are linked to danger and power as well as desire. Red light is known to blur imperfections and beautify, that’s how it came to its initial use in red-light districts. I’m quite interested in that intersection between desire and shame, the desire to look and the shame of the act itself. Now I’m focusing on two different spaces for my new work; one space is captured as an intense blue environment, which has little to do with the color’s more traditional calming connotation, yet it preserves the mysteriousness of the tone. The second space is captured in this almost toxic yellow light, which is a lot more alarming, a warning sign of sorts.

NB: So what is the role of shame in your work?

NW: Shame is a compass and a productive force that leads me into unexpected territories with vulnerability and courage. Behind that which we’re ashamed of, lies something complex on how we wish to see ourselves, the sticky stuff. I spent a lot of time hiding that I grew up in socialist blocks in Yugoslavia during my early childhood. These were self-sufficient towns inspired by the Swedish model called The Million Programme, capsules where you didn’t really have to leave an area, secluding people and pushing them towards the edge of the towns near the highways. The social housing situation in London was handled very differently, but I still find the location of Westway flyover and its surrounding neighborhoods (that I’m working with for my upcoming solo exhibition), strangely familiar.

NB: Is your work always created in series? How do you determine the beginning and the end of a series?

NW: I feel like every space I work with becomes one completed work. For example all of these new paintings that I’m working on, capturing a car park and a football pitch near Westway, are almost acting as a scenography of the place into which the viewer will walk in. So the space is mapped out and it becomes a ‘closed chapter’ in a sense. One series opens up a door into something new that naturally leaks into the next. It’s quite open-ended and flowing, and that’s one thing with painting that’s quite been quite amazing for me, like no other medium, it’s really leading me and I’m not in charge.

NB: Can you tell us more about what you’re working on, or any other exciting projects in the future?

NW: For my new show opening in November at Nicoletti Contemporary here in London, I took inspiration from the surroundings of London’s Westway overpass, a massive retrofuturist-looking construction, about which J. G. Ballard (author of Crash) wrote from a dystopian angle. I’m interested in how two completely different spaces intersect: a car park and a massive football pitch. I consider it as one interconnected unit because of how one is stacked on top of the other, but also because of how it’s socially used. Initially I got drawn to the incredible scene of a car park full of black cabs getting a car wash all at once. I later found out about the weekly ritual of five taxi drivers bringing in their cabs for a wash while they went upstairs to play soccer. This started my exploration of the space and then I added my own elements like the world of this fictional character, Wanda, and her admirers that are using the car park as a religious venue (which is actually inspired by activity taking place in one of the car parks where my parents live.) I will be also screening my first short film as part of the exhibition, which feels like a step closer to what’s been in the works for a long time.

I am also absolutely stoked about several shows scheduled in the new year and conversations open in New York which I can’t wait to pick up once I move back in a couple of months, after nearly four years in London.

September 1, 2022

Artist to Watch

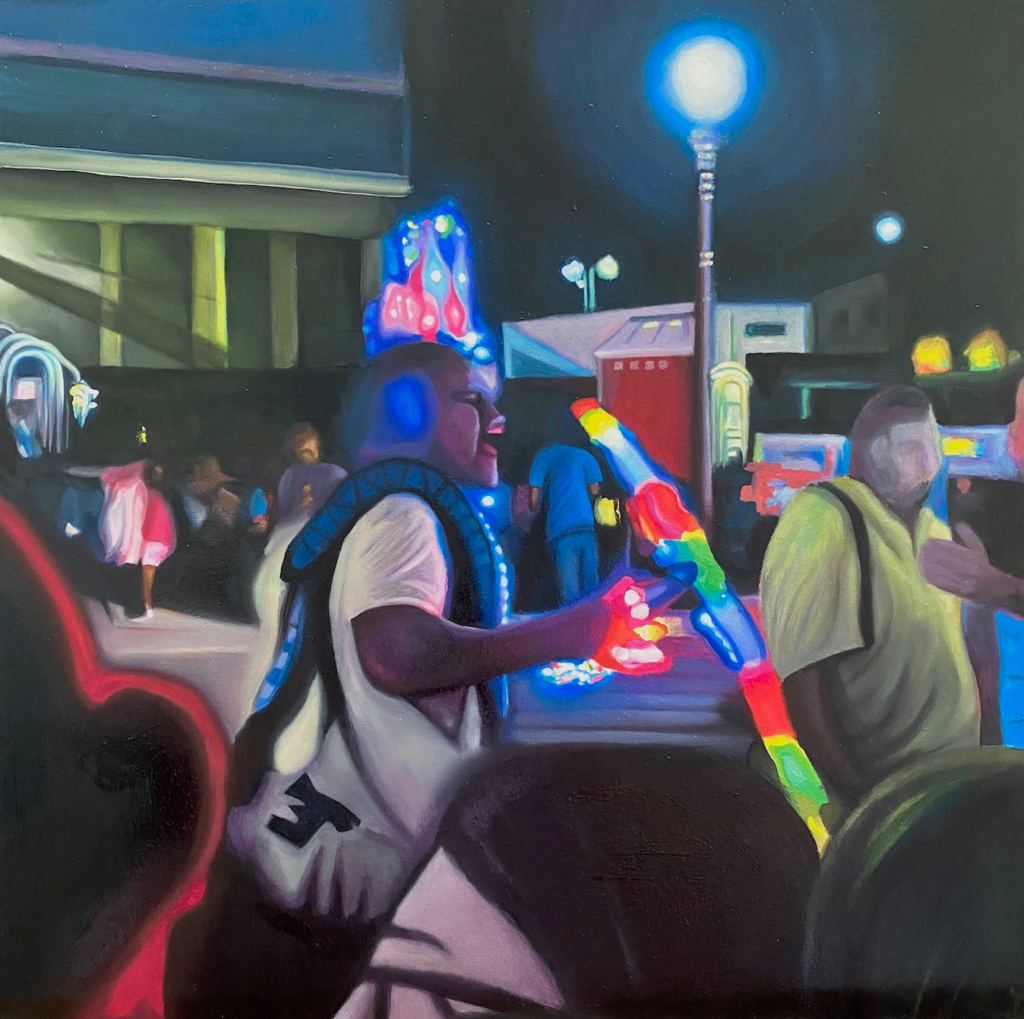

MARIKA THUNDER

NB: What is your earliest memory of art?

MT: I was very lucky as a child because I’ve been surrounded by art for as long as I can remember. Art was never identified as a separate entity since it was so integrated in my daily life. I went to a Waldorf school where various arts were embedded in the curriculum such as painting, singing, theater, woodworking, etc. However, because I was always engaged in some sort of creative activity or project, discovering my own passion and voice was a heuristic process.

NB: What is your greatest creative inspiration?

MT: I would say my lived experiences and the internalization of them. Every now and then you come across an artwork that enlightens you by offering a new perspective, or peek into a new reality created by the artist. Such artworks show the magnificence of human creative capabilities and their impact, which inspires me to achieve that in my work someday. Since I can only draw from within my own perspective to create, whenever I hear from someone that my work resonated with them it is incredibly rewarding to me as an artist.

NB: How do you incorporate your own personal lived experience into your practice?

MT: I am very interested in the human psyche and the subjects of community and faith/spirituality. When observing people in strikingly different environments and social groups, I try to track the consistent underpinnings of how a person develops within their community. No matter how different the circumstances, our innate drive leads us to seek purpose and passion within a community. It is also through faith and spirituality in these communities that a person may find their own feeling of fulfillment.

The particular images that I choose as reference for my works are extracted from my experiences living in very different communities. They’re not really determined by a conscious decision but rather by ontological circumstances that lead me to an intuitive choice.

NB: What are your thoughts on art and pop culture, and how the two areas both intersect and diverge?

MT: The two forever seem to be enmeshed through a self-perpetuating cycle of one reinforcing the other’s production- regardless of conscious intent. Even if there’s no obvious reference to or extraction from pop culture in an artist’s work, pop culture influences the environment an artist exists within and inevitably provides context for the audience’s interpretation of the work. Over time it’s also been interesting for me to observe how semiocapitalism and object fetishization has shown up in art.

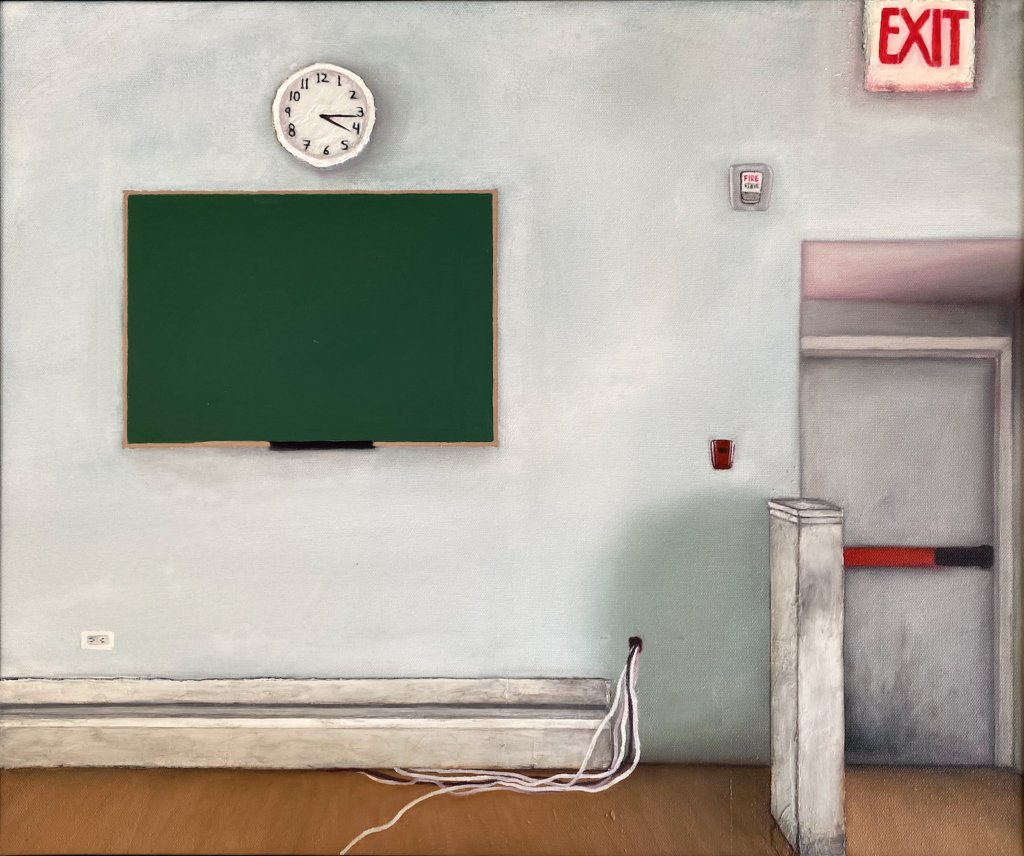

NB: Can you tell us about any upcoming works or projects?

MT: I’m working on a couple. I am painting a series of doors and interiors inspired by the ones I saw at an all-boys Yeshiva boarding school I visited in Yonkers, New York. There was a sacred energy present within the walls that’s generated by the boy’s dedicated practice to prayer and studying The Torah. You could feel a divine presence, which made me hyper-aware of ethereal lights and the smudges and markings on the walls indicating the presence of physical bodies passing through them. I wanted to see if I could make art that could evoke a similar experience.

I’m also working on some paintings that are inspired by photographs I took of crowds at a big street parade in Corpus Christi, Texas when I lived there for a couple of years as a teen. I’m spending a lot of time in the studio making work for my upcoming solo exhibition in January 2023 at Nina Johnson Gallery in Miami Florida.