October 5, 2022

Artist to Watch

NANA WOLKE

NB: What are your earliest memories of interacting with or experiencing art?

NW: As a kid and only child surrounded by adults I spent a lot of time on my own, often drawing, as that was the sort of medium that came quite naturally to me. My primary school teacher picked up on my enthusiasm for art and enrolled me in several different competitions, so I had a few experiences showing my work early on.

The other big influence came from being glued to the TV set during the post-socialist Slovenia of the early 2000s. Back then, the shift to the capitalist embrace of US culture was something that I was absorbing rapidly, always imagining this near fantastical world behind the screen. This thin line between reality and fiction is something I continue to examine in my work today.

NB: What is enticing about painting as a creative material for you?

NW: My undergraduate education in Slovenia was very traditional, an academy style of program, where we had nude models and figure drawing classes, very rigid and structured. My professors thought of painting as something that had already been done. Video and installation were much more common and although painting was still treated as dead, it was also regarded as a craft of the highest order that needed to be studied in excruciating detail. I was distracted from painting for a year or so, but I naturally gravitated back towards it. I don’t believe you really get to choose the tools with which you explore and work through things.

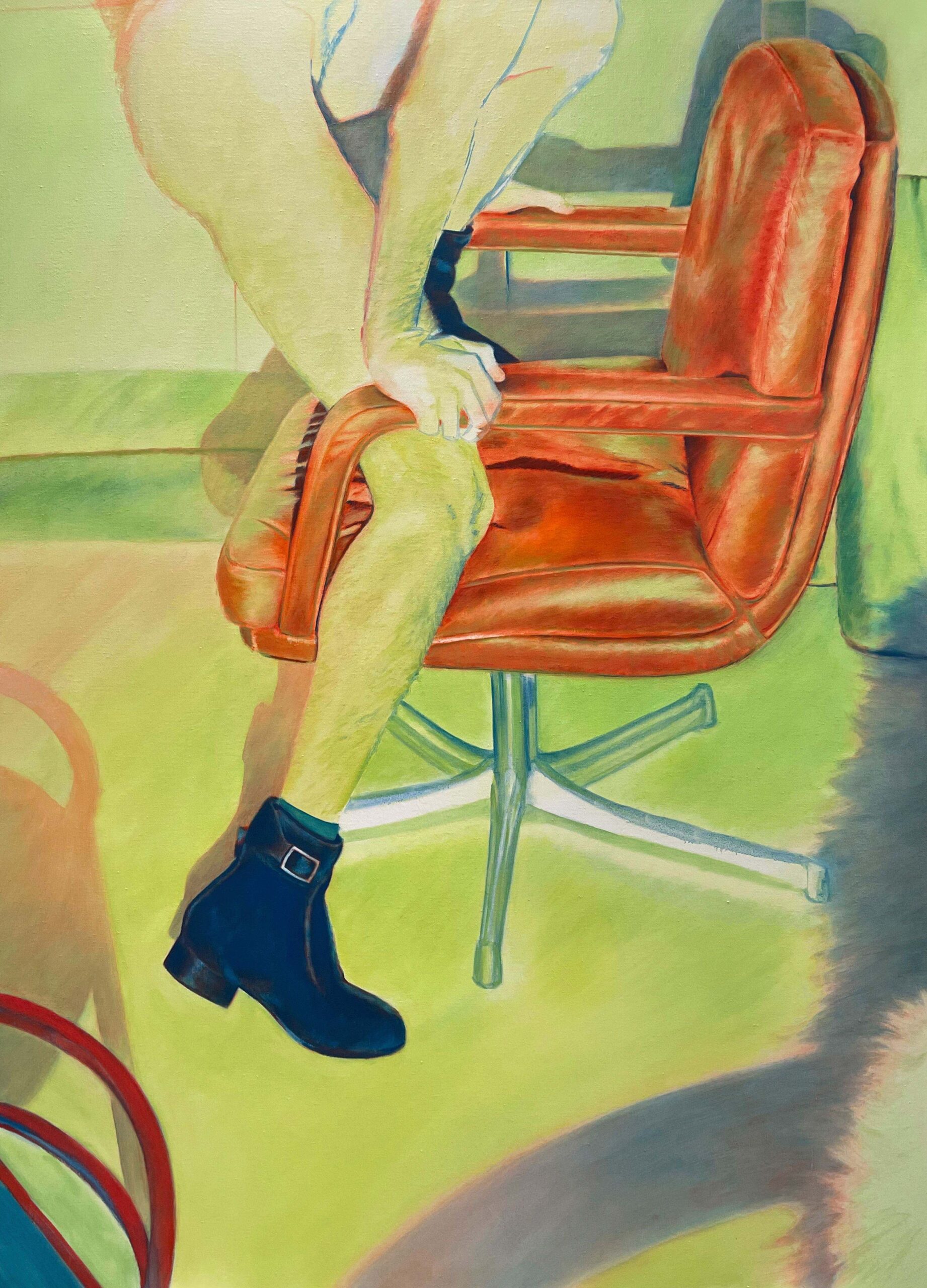

Today I’m most excited about the element of time in painting, which is perceived as much more permanent than, for example, a freeze frame from a film or a photograph. Bringing in the logic of a slippage of a moment (the wrong frame, rather than the climactic moment itself), as well as incorporating other elements like sound, shifts the viewer’s perception of time and space within the work and away from more traditional conventions of the medium.

NB: Your work borrows from the visual language of cinema, what kind of influence does moving image have in your practice? How do you arrive at the visual references used in your work?

NW: I’ve always been excited about moving image, especially cinema, but it took me quite a long time to understand the full potential of how it could play a role in my practice. Around the time when I was graduating Goldsmiths, I started working with specific locations and setting private performances. I would photograph both real and scripted situations, recording atmospheric sound and other material evidence of the setting to use as reference for my work, and as inspiration for sound pieces and prop-like sculptures. Really, my works are first and foremost artifacts of these private events.

The spaces that I gravitate towards are often transitional spaces, historically pushed to the fringes of cities or fully operational when most of us are asleep; from short stay hotel rooms and public garages to inhabited apartments, and above all, the people who frequent them.

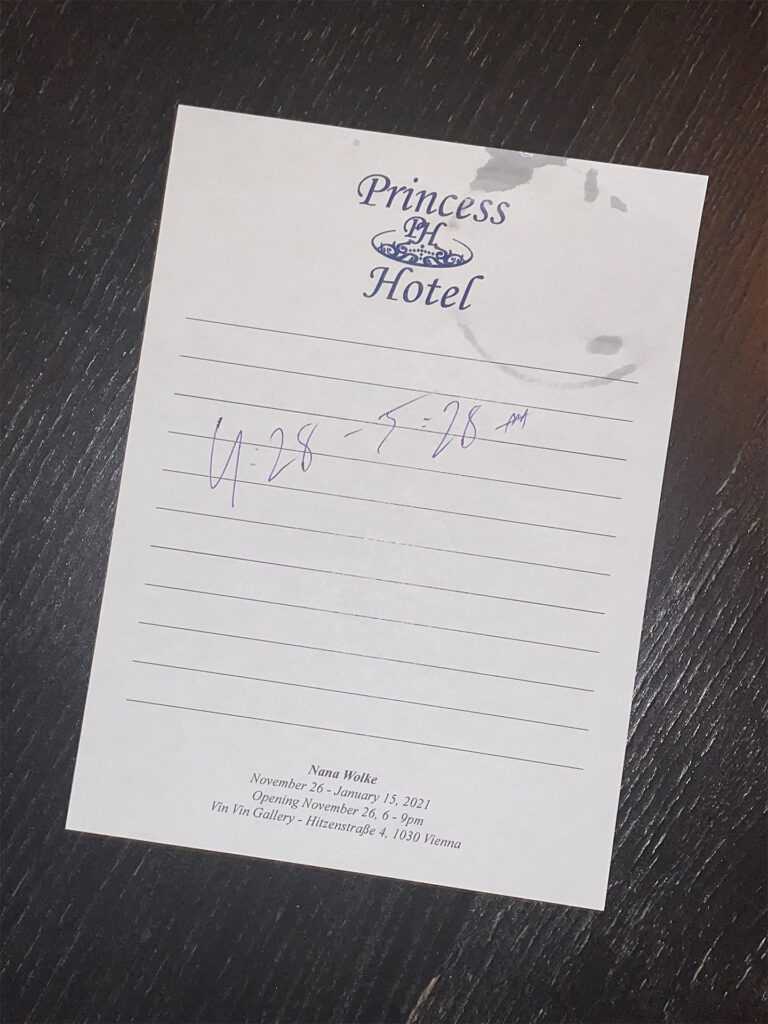

One of the spaces I recently worked with was a two star hotel in Kings Cross where I rented out a room several times over a period of a month to familiarize myself with how people used the space. Then I developed my own fictional narrative, a meeting of two potential lovers scheduled between 4:28 and 5:28 AM. I brought in actors – which at the time were really just my friends and we responded to this context together during what seemed to be a nutty experiment. The nature of the work is pretty fast too since we never have permits. I take the photos with my phone and use hunting lights instead of proper film lights which give a familiar cinematic effect but are easier to carry around.

NB: Your paintings have a characteristic monochromatic palette. What informs and affects the choice of color? In what ways do you think of color to convey different emotions and scenarios?

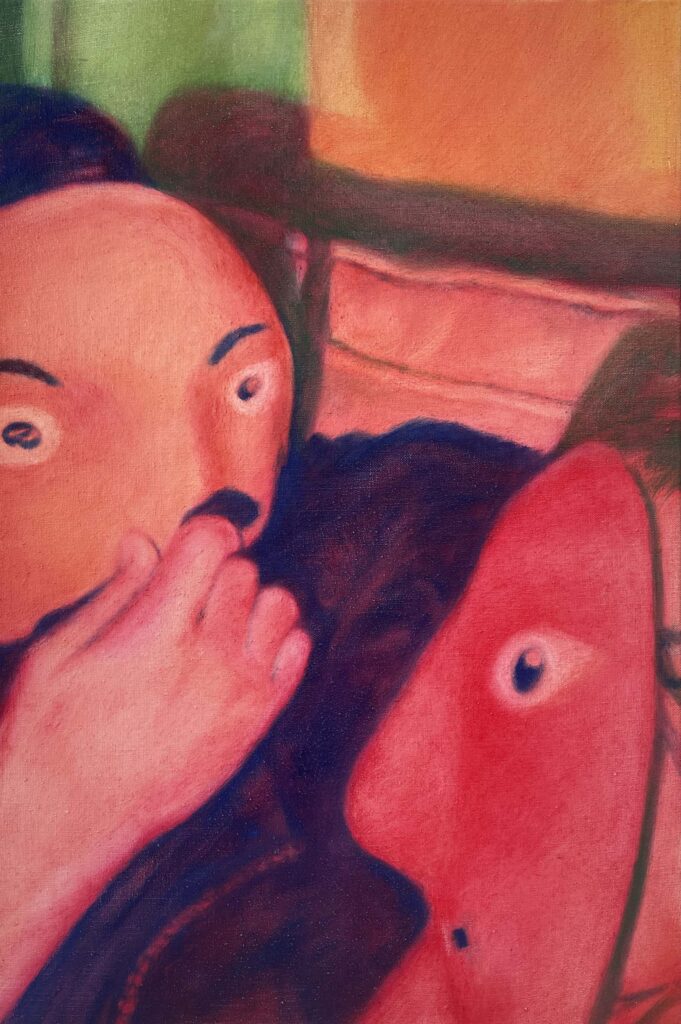

NW: The color range actually comes from me using hunting lights to stage with. These small handheld torches have an intense beam and come with four different color lenses – red, blue, green and yellow. I consider the kind of implications that colors have in terms of how the space is going to be portrayed, what kind of atmosphere it will create, and consequently how the viewer might approach it.

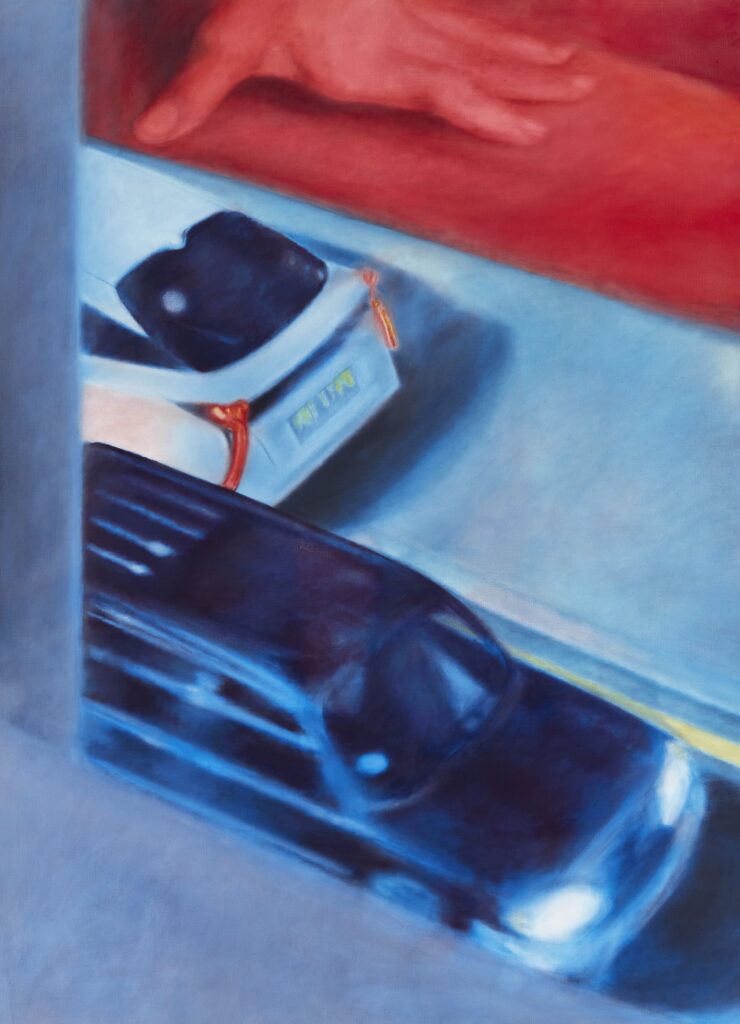

I was initially drawn to the color red, which both in art history and cinematic language, but also daily life, has a lot of different connotations that are linked to danger and power as well as desire. Red light is known to blur imperfections and beautify, that’s how it came to its initial use in red-light districts. I’m quite interested in that intersection between desire and shame, the desire to look and the shame of the act itself. Now I’m focusing on two different spaces for my new work; one space is captured as an intense blue environment, which has little to do with the color’s more traditional calming connotation, yet it preserves the mysteriousness of the tone. The second space is captured in this almost toxic yellow light, which is a lot more alarming, a warning sign of sorts.

NB: So what is the role of shame in your work?

NW: Shame is a compass and a productive force that leads me into unexpected territories with vulnerability and courage. Behind that which we’re ashamed of, lies something complex on how we wish to see ourselves, the sticky stuff. I spent a lot of time hiding that I grew up in socialist blocks in Yugoslavia during my early childhood. These were self-sufficient towns inspired by the Swedish model called The Million Programme, capsules where you didn’t really have to leave an area, secluding people and pushing them towards the edge of the towns near the highways. The social housing situation in London was handled very differently, but I still find the location of Westway flyover and its surrounding neighborhoods (that I’m working with for my upcoming solo exhibition), strangely familiar.

NB: Is your work always created in series? How do you determine the beginning and the end of a series?

NW: I feel like every space I work with becomes one completed work. For example all of these new paintings that I’m working on, capturing a car park and a football pitch near Westway, are almost acting as a scenography of the place into which the viewer will walk in. So the space is mapped out and it becomes a ‘closed chapter’ in a sense. One series opens up a door into something new that naturally leaks into the next. It’s quite open-ended and flowing, and that’s one thing with painting that’s quite been quite amazing for me, like no other medium, it’s really leading me and I’m not in charge.

NB: Can you tell us more about what you’re working on, or any other exciting projects in the future?

NW: For my new show opening in November at Nicoletti Contemporary here in London, I took inspiration from the surroundings of London’s Westway overpass, a massive retrofuturist-looking construction, about which J. G. Ballard (author of Crash) wrote from a dystopian angle. I’m interested in how two completely different spaces intersect: a car park and a massive football pitch. I consider it as one interconnected unit because of how one is stacked on top of the other, but also because of how it’s socially used. Initially I got drawn to the incredible scene of a car park full of black cabs getting a car wash all at once. I later found out about the weekly ritual of five taxi drivers bringing in their cabs for a wash while they went upstairs to play soccer. This started my exploration of the space and then I added my own elements like the world of this fictional character, Wanda, and her admirers that are using the car park as a religious venue (which is actually inspired by activity taking place in one of the car parks where my parents live.) I will be also screening my first short film as part of the exhibition, which feels like a step closer to what’s been in the works for a long time.

I am also absolutely stoked about several shows scheduled in the new year and conversations open in New York which I can’t wait to pick up once I move back in a couple of months, after nearly four years in London.