June 29, 2021

Artist to Watch

ANDY MISTER

NB: You received your MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Montana, in addition to studying English Literature (and Philosophy) during your undergrad years at Loyola University in New Orleans. Can you speak to how your studies in this area influenced your art and your creative practice today?

AM: I was really into the visual arts, and into making art as a kid. As a teenager, I went to an arts high school. I wasn’t a huge reader until the end of high school. I didn’t really know what to study in college, so I just signed up as an English major. Taking English classes in college taught me how to think critically, I don’t think I had ever really thought critically before that time. It really opened my mind up different ways of thinking about language and information that I just had never really considered before. I think it might have been in my first English major class — our professor asked each person in the class to explain the difference between a window and a door. And it’s really hard to do! You can do it in a utilitarian way, or you can describe it physically, but it’s really hard! A lot of times, the way you describe a window and a door it sounds like they’re the same thing. As an 18 year old, that slipperiness of language really struck me. That really opened up a lot of ways of thinking, for me, that I hadn’t encountered before. For my MFA in Creative Writing, my specification was poetry. There is this famous story where Edgar Degas was talking to the poet Paul Valéry, and he said to him “I am going to write all of these poems. I have all of these great ideas. I have so many ideas that my poems are going to be great!” Paul Valéry famously replied: “well, poems aren’t made out of ideas, they’re made of words.” In the visual arts, similarly, a painting or a drawing isn’t made of images so much, or even ideas; it’s made of material. For me, my drawings are made of marks. In my work I try to focus on mark making in the same way that words are the fundamental element of writing.

NB: I never really thought about the artist’s process of mark making as being intertwined with the words of poets, and I see there is a very interesting parallel there. Poetry has been so integral to the visual arts — thinking of artists like Kiefer — it is always there.

A lot of your work examines the process of appropriation. Can you talk a little bit about that, and how the works question the way meaning is either created or lost throughout this process of appropriation? Can you tell us a little bit more about what drew you to investigate this topic?

AM: For my generation a lot of the music I listened to as a teenager involved sampling, taking pre-recorded pieces of music and stitching them together to create something new. Also, a lot of elements of the design world (also around music) involved appropriating film stills, and things like that, in graphic design. Before I knew that appropriation was a thing in the arts — the Pictures Generation comes to mind — through osmosis, I had already accepted these ideas of appropriation that perhaps my parents’ generation would have found questionable, or they wouldn’t have considered a real, original piece of art. For me, it was natural. Later on, when I did find out about the Pictures Generation — Sheri Levine and Richard Prince — it didn’t have to be explained to me, it was just obvious. In my own work, I consider all this visual material, whether it’s photographs that I take, something created from life, or something that I find — it’s all grist for the mill of your artistic process; there isn’t a hierarchy. In my writing and my art practice, I’ve always felt that there should be a democratization of source material. I feel that same way in my own work regarding the images that I choose. They’re all of equal importance, there isn’t one image that is more important than another. It’s just a question of how you use the images, and how — when you present it to an audience — people bring their own experience to the work and interact with it.

NB: In terms of the images used in your work, drawn from outside sources, what attracts you to certain images, and not others? I know you just touched on this a little bit.

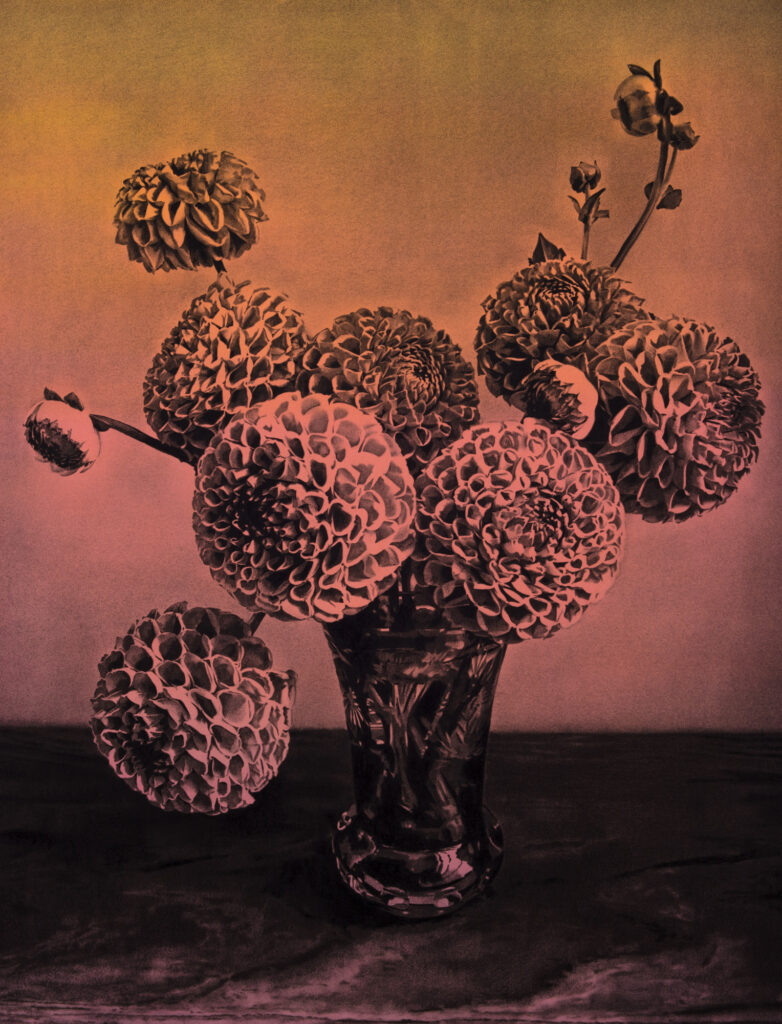

AM: A lot of the work that I was making at a certain point in my career was socio-political, or historical. I was interested in different historical moments, and I would then research and look for specific images that represented those moments. For example: using a photojournalistic image from the Vietnam War, cropping out a weird detail from it, and blowing it up. Similar to the Michelangelo Antonioni movie Blow-Up. Expanding the image into something new that isn’t recognizable from the original. Back then, the subject matter was important to me, even if it was somewhat obscured in the final piece, or in the process. Over time, I became a little less interested in the historical placement of an image, and more interested in the immediate aesthetic enjoyment of images. I started thinking about taking Pictures Generation moves, or relationships to images, and connecting it back to more classical art historical references. Using content like traditional landscape, or traditional still life, but instead of replicating them from life, or en plein air, finding old photographs and again manipulating and translating them into drawings and paintings. That is how I interact with the images now. I try to find a feeling that I get from a sourced image. I then scan it and try to heighten it and crop the photo to make it into my own thing; I then further make it my own through translating it by hand.

NB: Is it drawing, is it painting, or is it a mixture of both?

AM: I’ve gone through a few different material processes. The majority of the work that I do now uses watercolor paper that I paint washes on, I will then use carbon and charcoal pencils on top of that — and sometimes pastel — to draw an image. As the final step, the paper is mounted to a wooden panel, so it’s not framed and will instead sit on the wall like a painting. It is in this liminal space between painting and drawing, which I feel lets me have the best of both worlds. I really do enjoy drawing, and I enjoy doing things by hand, but I also like a lot of the material elements of painting, such as texture and form, that you don’t totally get with drawing. There is almost a three dimensionality that you lose with drawing. Originally, when I went from making paintings to drawings, I was making graphite pencil drawings on paper. It was exciting to pare the materials down like that at first, but then I became interested in figuring out a hybrid of painting techniques and drawing techniques.

NB: Can you speak to your two most recent residencies, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council in New York, New York and the Bemis Center of Contemporary Arts in Omaha, NE? How were these experiences? How did they foster growth, creativity and opportunity for you as an artist?

AM: They were really great. I didn’t go to graduate school for the visual arts; a lot of people that I know, especially in New York, came with a built-in group of people with whom they attended graduate school. I do feel like that is one thing I did miss out on. Doing residencies was my first glimpse into what that sense of community in making your work is like; meeting other people who were making very different work, with very different ideas about art making, and bouncing my ideas off of them in a structured setting. It was really great. At the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC), I did this project where I drew a drawing of a different political figure every day of the presidency. It was eventually made into a book called Heroes and Villains. I had some ideas like that, to create conceptual pieces, but I had never really had the means to actually make it happen. And LMCC gave me the space to do that. The Bemis Center was also really great; it’s in Omaha, Nebraska. It’s a really beautiful building with really amazing studios, they give you a stipend, and you go there for three months. At that point, I had been working a lot of day jobs and creating work at night and on the weekends. My time at the Bemis Center was the first three month stretch of uninterrupted art making that I had experienced in years. Right after that, I did a solo show at Geoffrey Young Gallery in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and I had created the work for that show at the Bemis Center. That whole period was a really great time for me.

NB: Can you tell us a little bit about what you have upcoming in terms of shows, residencies or projects?

AM: I just had a solo show close at Rebecca Camacho Projects in San Francisco. And now I am making work for my next solo show, at Lowell Ryan Projects in Los Angeles. It opens in February 2022. They have a really beautiful new space that has these amazing high ceilings. I am making some of the biggest mounted panel pieces that I’ve ever made for this show — they’re around 60” x 80” so they’re pretty big! It takes a lot of time to make pieces that big, so most of my energy is going into that right now.