NB: So, what are some of your earliest memories of making art, and how has it evolved to where your practice is today?

S: I would say my earliest memories are in my grandmother’s living room, just rummaging through her magazine collection. She was an avid magazine collector, like Ebony, Essence, and Jet. I would pull photographs out of those pages , use them as references and start to sketch. One of my most profound memories is when I was in kindergarten, I won the school-wide competition where we had to sketch Philadelphia’s independence hall with gold leaf. I won, and that work was exhibited at the Philadelphia Art Museum. It’s a fun way to trace my skills back to my earliest years.

I’ve always lived in creative households with both my grandmothers. One grandmother, who I would say aligned more with photography, had a photographic practice, even though she probably wouldn’t call herself one. She was the family archivist and was always documenting everything, which is something that’s in my work today, working with found materials and archiving. But then I also had a grandmother who was into literature, poetry, and singing. Initially, I thought that I was going to be a singer, a performer, because she would take me around to auditions and talent shows. I was in the gospel choir growing up, so I was always in and around the arts, even though I grew up in an area where the possibilities of that sort of manifesting into a professional career wasn’t something that was thought of.

NB: So, drawing from that, can you walk us through your research process and how some of the references materialize in your work?

S: Honestly, when I start a new project, it usually stems from a personal experience or a specific curiosity. I then build a framework around that using historical or theoretical research that has sparked my interest. For example, with my performance piece for Performa, Notes Towards Becoming a Spill, it was very much an autobiographical exploration, a journey of becoming, that drew from my experiences growing up and trying to find spiritual balance amidst the complexities of the religion I was raised in. There’s always a personal thread that serves as the spark, which then leads me to explore different kinds of scholarship that either emerge from or resonate with that personal narrative. In the case of that performance, my research was shaped by ideas around gender performativity, Black aquatic histories, and the symbolism of the color blue.

Once I have that foundation, I start sketching. Sometimes it’s in a notebook, other times it’s just on my phone, especially when ideas come to me after a night of dreaming. I also do a lot of visual research. I spend time in libraries looking through photography books, pulling references, and saving images into an archive I’ve built across my devices. It’s a habit I picked up during a high school internship from a mentor, and it has become central to how I think through form and composition. That combination of sketching and image collecting helps me see how the research starts to take shape in the work itself.

NB: So that kind of leads on to the next question: when working on a new piece, where do you begin? What’s really interesting for me, when I have encountered your work, is how you layer in these different theoretical or scholarly frameworks around your personal experience. One thing that really sparked my curiosity was Hauntology. Could you explain how you came to this concept?

S:Again, a lot of what draws me to these more philosophical frameworks really comes from lived experience. I grew up with a grandmother who believed our house was haunted, and as a kid, I believed that too. We would watch the History Channel and the Sci-Fi Channel together, and I started building an imagination around the hauntings we saw in those documentaries. It was always something I felt drawn to explore more deeply.

Before she passed, I was able to interview her about the hauntings she experienced from childhood throughout her life. Later on, while spending time in the library — I’ve always loved libraries — I came across the concept of Hauntology by Jacques Derrida. It is a philosophical idea about how the past leaves behind traces or residues that continue to shape the present.

For me, Hauntology is one of the most resonant frameworks for thinking about the Black experience because our lives are deeply shaped by histories that refuse to stay buried. You see it in generational memory, in cultural traditions, and in the lingering effects of systems that were never truly dismantled. Scholars in Black studies have written about how the archive often fails us, how it is incomplete, distorted, or violently silent when it comes to Black history. Hauntology helps make sense of that. It shows us that absence does not mean emptiness. There is weight in what is missing, and what has been erased still speaks.

In my practice, I work with materials that feel like carriers of those kinds of traces. I have experimented with expired film, red dirt, found objects, light, and glass; not to recreate the past literally, but to create space for what has been submerged to come forward. These materials hold memory, even in their decay or transformation. That mirrors the Black experience for me. Our histories are rarely linear or fully recorded, but they are deeply felt, always present, and constantly shaping how we move through the world.

NB: Then there’s also such a rich art historical narrative with blue and how that has manifested its way from ancient times through to the indigo plantations of the South and through art history. When you look at the blues in Rashid Johnson’s anxious men, there’s the Hauntology of the past in his anxious men work, which connects to the blue bead in your work, “Blue Shadow”.

S: Yeah, absolutely. There are so many layers to blue, especially when you’re thinking about it through the lens of Black cultural memory. I always say blue is more than just a color in my work. It is a mood, a presence, a kind of frequency. When you spend time with it, it opens up all these different pathways. There is the emotional register of blue, like blues music, feeling blue, that sense of longing or mourning. But there is also the material and historical weight it carries.

Indigo, as you’ve mentioned, has this deep history tied to the transatlantic slave trade and the plantations of the American South. That history lingers. You see it in Southern Black traditions, in spiritual practices, and in the way porches were painted haint blue to keep spirits away. All of that speaks to Hauntology in its own way. It reflects the idea that something from the past is still very much with us, even if we do not see it directly.

NB: Could you tell us about your most recent project in Philadelphia? I’d love to hear more about that.

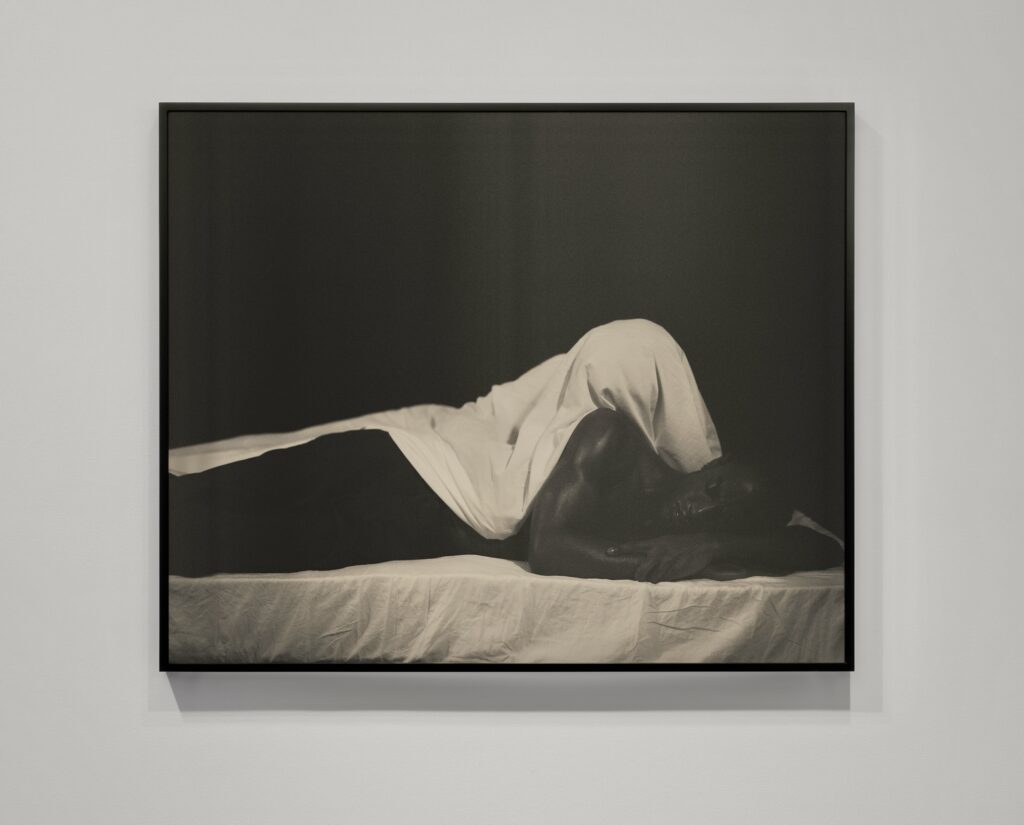

S: Yeah, so I’ve got my first show opening in my hometown at TILT, The Institute of Contemporary Image. It’s called People Who Die Bad Don’t Stay in the Ground, which comes from a line in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. A story about the haunted life of a former slave.

This show feels like a more layered continuation of the ideas I’ve been sitting with for a while, especially in terms of how I use photography. I’ve been experimenting more with expired film, found images, and archival materials, while also drawing from personal stories and memories that feel like they’ve been lost or overlooked. A big part of that is about the men in my family, like

my grandfather and great uncles who served in Vietnam. A lot of these photos are me trying to imagine what things might have looked like through their eyes, or what their emotional landscapes could have been. Some images feel like they belong to the past, some to the future, and others sit somewhere in between.

The show is mostly new work, but some of it was made alongside my last photography series as I traveled between the South and the North over the past five years. Bringing it all together now, it feels like things are clicking in a new way. I’m starting to see these threads more clearly and with a bit more emotional weight.

NB: So now that the show has opened, do you have anything on the horizon?

S: Yes, I have two major works coming. In April 2026, I’ll be debuting my first public artwork, a 10-foot-tall sculpture called Hold, here in Pittsburgh, where I live. Second, and equally exciting, I’m launching a digital humanities platform called Project Blue Space. This takes my studio explorations and pushes them into a more public, community-focused realm. The core of the initiative is to bring people together through programming and accessible research to explore the deep, often overlooked histories of water in relation to Black life.