June 2, 2021

Artist to Watch

DOMINIC CHAMBERS

NB: Can you share with us a bit about your experience with art as a younger man, leading up to your time at the Yale MFA program?

DC: Growing up, I always had a fondness for drawing. Mostly recreating characters that I saw in cartoons or in anime. I was a huge anime and comic book fan. I tried to find every opportunity to draw something. My love for drawing coupled with an incessant need to create something was heightened as I took frequent trips to the St. Louis Art Museum during school field trips. Like most black youth in impoverished neighborhoods, I couldn’t imagine a sustainable life in the arts. So, I decided that I was going to keep my artistic sensibilities to myself, maybe write short stories or write plays and keep them to myself. But I was dating a girl who told me that if I didn’t go to college she was going to break up with me, so I enrolled at a community college where I was exposed to the critical discourse present both in art history and the contemporary art world. I felt like I finally had a space to participate. From there on out, I learned about the Yale MFA graduate program and the Yale Norfolk School of Art residency. I set my sights on those goals because, in my mind, coming from a lower income family in the northern part of St. Louis, there was no middle ground for me to be okay; it was either, you stay where you are, or you go on to achieve the best. Having a naturally competitive and ambitious spirit, I decided that I wanted to be included in dynamic conversations and have my work respected by the artists and institutions that I came to appreciate.

NB: That is impressive, really impressive. Can you share with us a bit about the subjects in your figurative work? If you could also speak a little to your process, it would be great to get that context.

DC: A lot of the subjects in my paintings are all friends of mine. They are mostly friends that I met in graduate school. The idea, in a way, is that the paintings are a timeline of my life; the subjects grow up. There are collectors who have paintings of me with my long hair, then there will be other [collectors] who have [works] of myself with short hair now. So, in a sense, I am a living subject in these paintings. The process is really one of community. I will reach out to my friends and ask them to model for me, they are often enthusiastic to do so. I think that collectively, we have a shared appreciation of seeing ourselves in moments of leisure and rest. In that way my friends are very supportive of my project. I draw a lot; I’ll sketch some things out in my sketchbook. I’ll text a couple friends “hey, do you have maybe five or 10 minutes? I’ll come to you” and I’ll share with them my compositions and ideas. My friends are great, they’re flexible and willing to work with me. An old professor once said something that I never forgot: “the good thing about being an artist is that people assume you’d be weird anyway,” so you can just be yourself. It’s been working out.

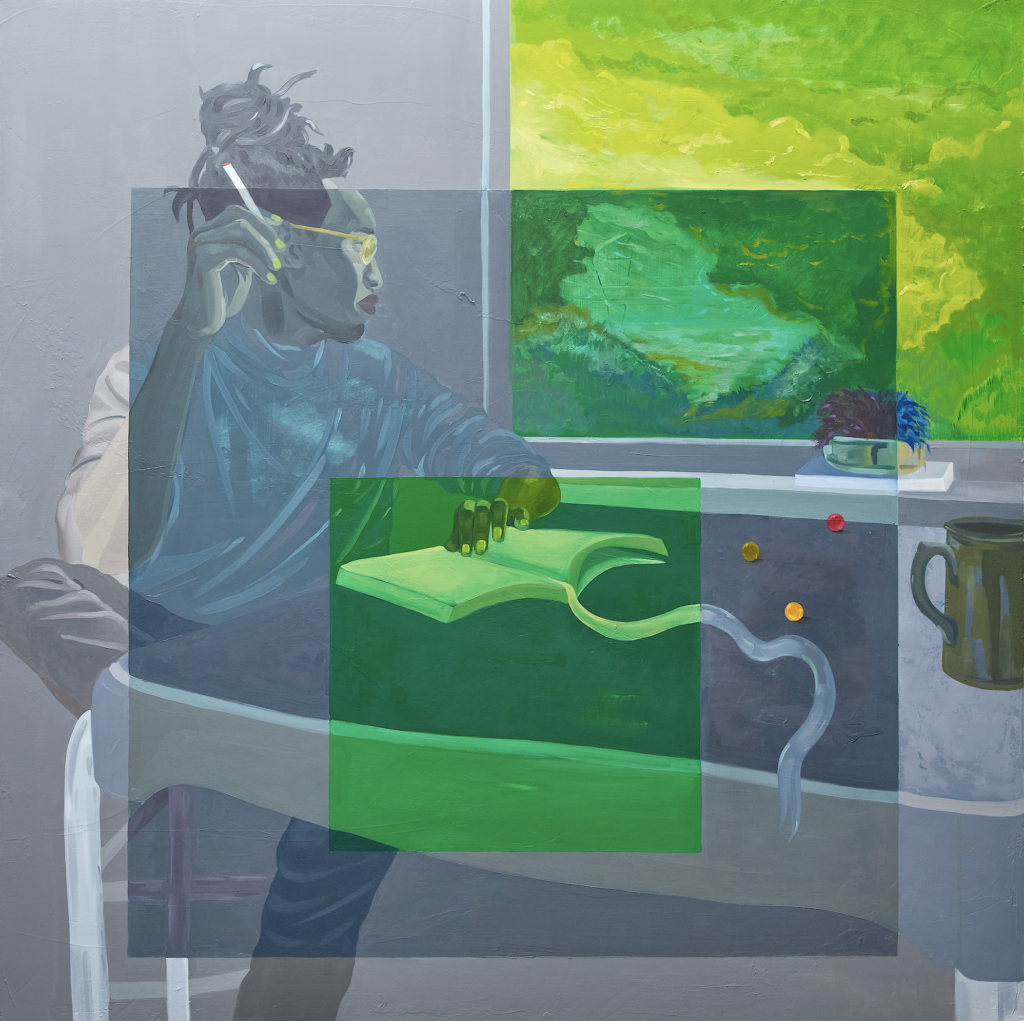

NB: What are your thoughts on figuration and abstraction? We’ve seen the two approaches intersect really beautifully in your work, particularly in the After Albers series. It would be great to discuss this from an art historical perspective.

DC: When I first started painting, I took foundational courses which focused on painting from observation. While at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, I made a lot of minimalist, abstract paintings. My paintings were just one color; they were all about my relationship to color. There was no image, the work was all about surface, color and very objective approaches to making a painting. As my process evolved, it made sense that the abstract elements followed me into my figurative work, even if you consider my relationship to the color in my current paintings. It’s certainly a byproduct of my past investigations and love for color and color theory. I understand I can capture a color without too much fuss – I’ve been exploring color for such a long time. With regards to the After Albers series – they take inspiration from Josef Albers, the modernist painter, and his homage to the square paintings, in addition to his theories concerning color. I think that in society, we kind of treat bodies like abstractions anyway, so, for me, there was this beautiful symmetry between our bodies and what we perceive to be our identities — as our identities are contextual. Josef Albers’ investigation with color, and color being a product of relationally; Our understanding of a given color is relational. The idea is, that if you were to orient two colors next to each other, they could influence one another and consequently affect the eyes’ ability to interpret what it is that we’re looking at. The two colors can change; they could even create a third color entirely. In a way, we are like those colors and I found that my body and my identity function very similarly. My Blackness has a particular cultural and social specificity attached to it in the context of America. But if I were to go to Africa, my body would be read in a very different way; because the racial logics and paradigms are different. Art historically, that’s where I was pulling from, but merging the concerns and examinations of Josef Albers’ objective exploration of color relationships with the contemporary concerns surrounding identity politics that we’re all currently negotiating.

NB: I have never heard anyone speak to Albers and identity politics in such an artistic way.

DC: When it comes to the figurative works, too, I am utilizing palettes from Josef Albers paintings. I’ll have a stack of color swatches, I have hundreds of them. I try to get the colors as correct as I can, as close to the Albers paintings as I can. They’re not in front of me, of course, so I have to rely on my own color sensibilities. I’ve studied the history of color, in Marcia Hall’s book Color and Meaning, and brought in different painting strategies that I thought, within the high and low Renaissance, would compliment the modernist aesthetic of Josef Albers, or, as it relates to my paintings. Josef Albers paintings are singular swatches of color, mine are figurative, which means that the use of color would be expansive. I thought to myself “How can I create harmony with color that creates a dynamic image but doesn’t lose the monochromatic flatness of Albers painting.” So I started thinking about different modes of painting such as unione, which is used, historically, to create harmony while not losing the chromatic integrity of a color. It has been good for me to think of the color spectrum that Josef Albers was working with — for example, Albers paintings are three colors. Of course, when I engage with a body, there are different shadows and shapes that compose the body. Utilizing unione makes the most sense for my approach in solving that problem, because you’re creating harmony. You would work from the middle of a color, and you expand out. They are drawing a contrast in those paintings. If the outer rim of a Josef Albers painting is a teal blue, or an ultramarine blue, utilizing unione, I can work from that blue and create a sense of harmony so that the product the viewer sees in my paintings, still looks as though it is a solid, framed color.

Basically I minimize the color spectrum, to a degree so that there aren’t any jarring contrasts. It’s great for getting a huge range of values for something as flat as [one specific shade of blue]. That is one way I’ve been approaching it, along with maintaining a more critical eye for how I am building out the figures as they relate to, or are an homage to, the square composition. Sometimes the figures are sitting down, because I am thinking about their arms, and thinking about how their body can create a shape within the square format, as well. There is also this play between the body itself becoming a form of abstraction. If you consider a painting like After Albers (Seeing Through the Dark), you’ll notice Kevin’s body becomes a triangle, in a sense, because we’re looking over his shoulder.

NB: Is that Kevin Brisco?

DC: Yes, it is! In the most recent After Albers painting I did, Seeing Through the Dark, you’ll notice that Kevin’s body becomes a triangle. There is a play between both the figure and ground reversal, as well, but utilizing the body also to add an extra element of abstraction to the painting.

NB: Could you speak a little bit about how that color theory process also extends to your Wash paintings?

DC: The Wash paintings were born out of my interest in this idea of the ‘veil’ that W.E.B. Du Bois talked about in his book The Souls of Black Folk. In addition to depicting images of black leisure, I am also concerned with critical history, art history and literary narratives. A lot of my work considers surrealism, and its literary counterpart magical realism. Because I often see the Black experience as being a surreal one. When Du Bois talks about the ‘veil,’ it’s essentially this metaphorical illegibility that’s cast over your character. This ‘veil’ is the curtain that separates the black subject from others and disrupts the opportunity to engage with said subject on equal and fair terms. For Black individuals, it is our skin that alerts others that we are different. A similar proposition, I think, can be applied to women: it’s also their body; it’s their gender. Often when men encounter them, their gaze is filtered through a patriarchal lens and consequently prohibits them from engaging with who that woman, as a person, could possibly be. Still, you don’t see the veil; you experience it. But through the lens of magical realism you could see it. That is what the Wash paintings attempt to address. You engage with these paintings that are these depicted scenes, but the splatter and the abstraction that ruptures the overall image is what we are engaging with, so, in a way, we are engaging with that ‘veil’: that illegibility, that curtain, that thin layer. When I make the Wash paintings, I’m using my body. I’ll often fill buckets of paint up and I’ll pour the paint on top of the painting, or I’ll slap them off; they’re much more physical. They have a different relationship with my body than the Primary Magic paintings or After Albers painting, which have a stronger relationship to my mind, because I’m thinking more (in terms of color theory).

NB: Are there any upcoming projects you’re excited about? Also, I understand that you’re a collector. I am curious to learn about your thoughts for the remainder of 2021 in both areas.

DC: I have a solo show at the Luce Gallery in Torino, Italy. The title of the exhibition is “Life and Its Ghosts” and it is about my shift in reality. Over the course of 2020 to 2021 I have been struggling with this dramatic shift that has happened within my reality, both in response to Covid and my growing profile in the art world. I found myself navigating new spaces and engaging with very different people. My external reality has also changed; I never imagined I would have a studio such as the one I have now. But I am still haunted by the ghosts of my past; life and its ghosts. I can’t escape it; I have a lot of anxiety. I use that word ‘ghosts’ specifically, and it’s because a ghost is something that has the potential to be encountered again, there is some kind of veracity to it, there is a body or presence to it; and that’s what my past has been for me. It still somehow lingers within my everyday life, despite my leaving St. Louis; despite being in the later half of my 20s. The show will negotiate those things, amongst other familiar concepts I’ve been working with.

Collecting, for me, is really important. I really think everyone should be a collector; artists are cultural producers. When you are collecting, or when you’re going to a museum, you’re collecting someone’s intellect; you’re collecting that mind. When you go to a museum, you go there to learn, right? You’re engaging with the intellect of all of these great artists across the spectrum. For me, I am a lot less concerned (and I know the market is huge) […] Black figuration, Black portraiture, and more recently Black abstractionists who are starting to get a lot more attention, too. As a collector, I am less concerned with those kinds of trends. For me, I want to know what your research is, I want to know how an artist reads their subjectivity. I want to know how an artist considers their own relationship to the world. When I reach out to a gallery to inquire about a work, the first thing I ask is: can I read the artist’s bio, can I see their CV? Is there any writing around their practice? Because, if I want to champion you, or if I’m going to invest in you, I want to see what you’re capable of doing. I want to invest in your project, that’s my role as a collector. I want to invest in your ideas. For me, that is the thing that fuels my own collecting. I have a very uncompromising eye, so I don’t collect everything. Because I know everything is not great. I also understand that the market is very fast-paced and with the pace the market moves at, that oftentimes forces some artists to produce things they might not necessarily be the most proud of, but they’re trying to feed the market because, you know, we all have lives and bills to pay. A small sacrifice to keep things going? But, as for myself, I really do believe in collecting what you love, but also maintaining a very critical eye to what you’re going to be living with. For me, as a collector, I think about that quite a bit.

NB: Could you share what you’re reading at the moment? What’s on your nightstand now?

DC: At the moment I’m reading a couple of things: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman, and Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain. Quiet was recommended to me by a friend and I’ve been enjoying the writing quite a bit. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is an incredible read! The writing is so rich. I read the Daily Stoic everyday, or at least I try to. There was a time when I was beginning to feel quite comfortable with my grief and sought out something to read, mostly as a temporary distraction and I came across a book on stoicism called the Meditations by Marcus Aurelius and I fell in love with its philosophical teachings. From there I ordered the Daily Stoic and haven’t looked back.